Camille Fischer

January 2026

for Temple Magazine issue 13

Smoked Garden

On the material fragility of opiates from elsewhere, gathered into a bouquet.

More than a wunderkammer or a cabinet of appearance cultures, the grand garden Camille Fischer composes shelters, from beds to borders, the variations of adorned beings, whose garments are identity made portrait, skin itself,” says Antoine Lavoisier from beyond the grave.

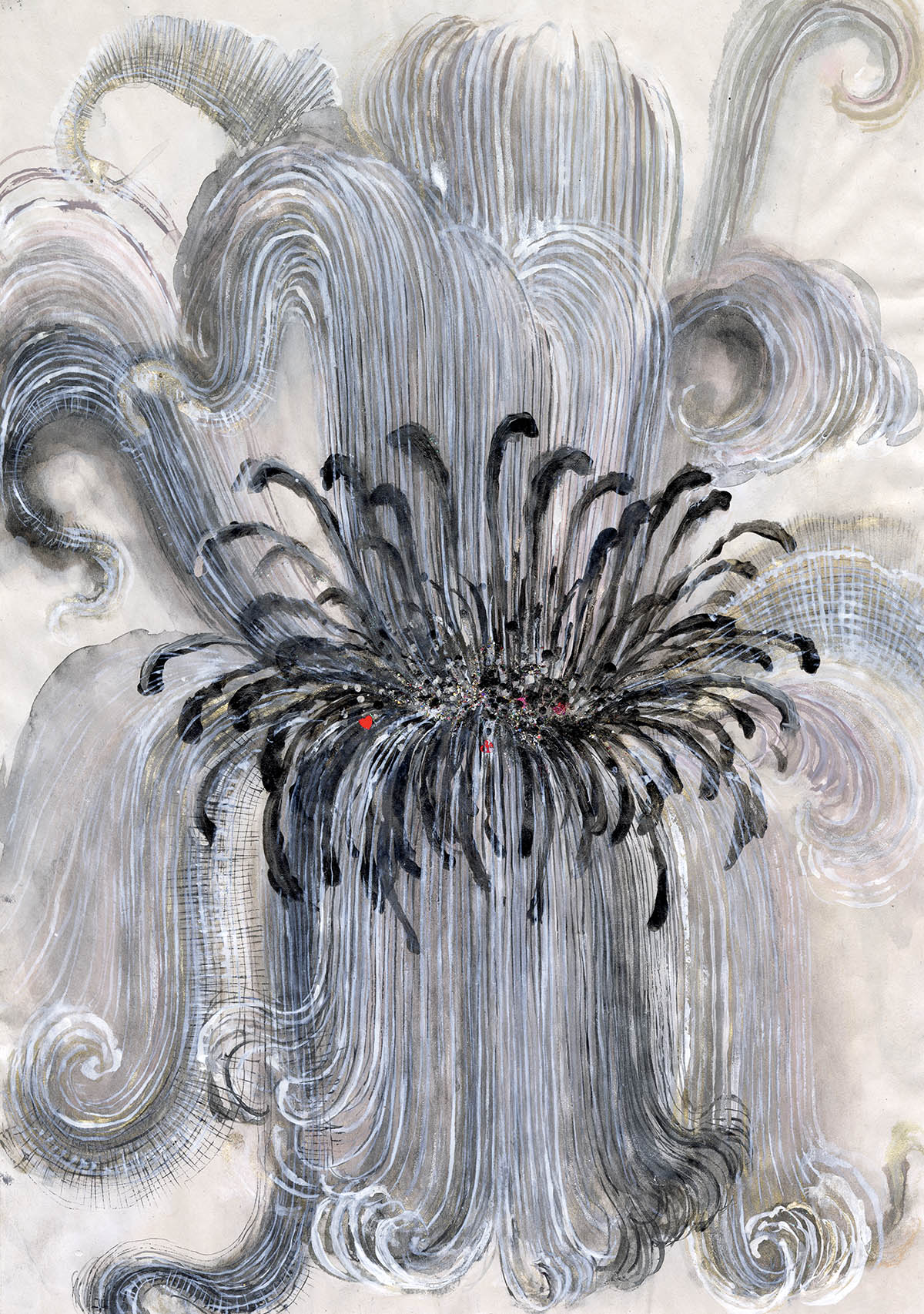

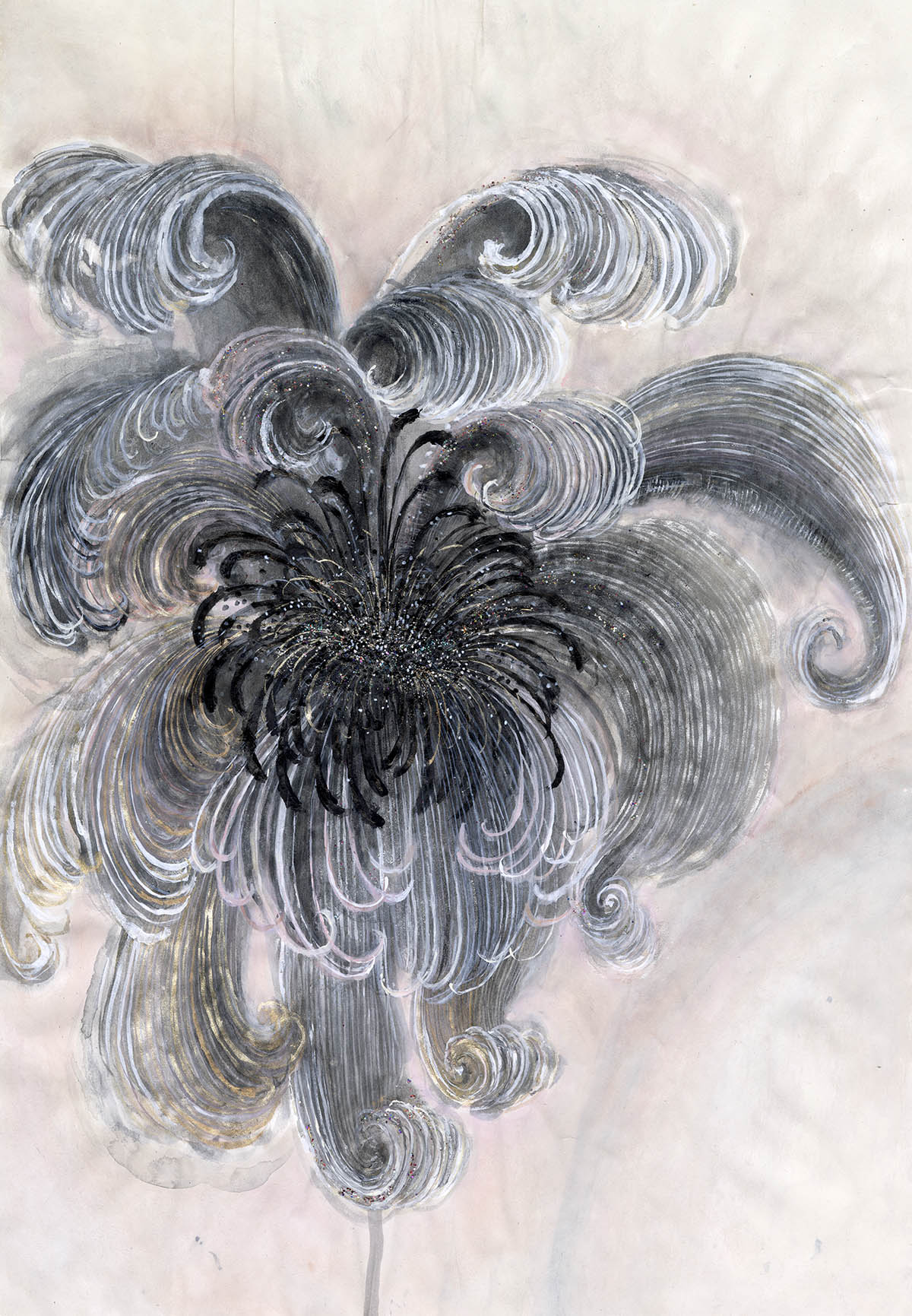

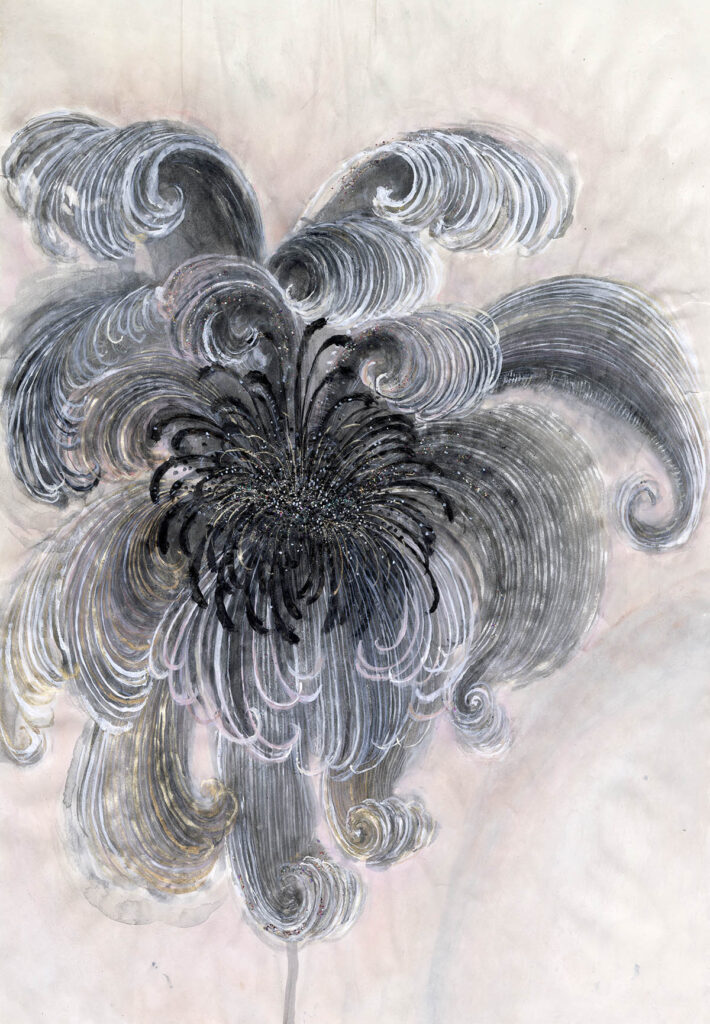

“And in this great cosmic bath, both potential and brimming with vitality, where what remains is the matter of what is to come, everything blooms and vice versa” he continues inwardly, not displeased with the positive synthesis he has just produced on the multidisciplinary practice of the artist he observes from his patch of intangible clouds. Indeed, in the in-between of a dreamed Rococo salon or the bedroom of the eternally adolescent collector, Camille Fischer’s ornamental system embraces every medium and blends them all together. A crepuscular theater, where each represented fragment reveals the fragile and supreme fruit of flora — the flower. Her gesture, in its broadest sense, explores these interconnections: both assembler and ornamentist, Camille reorganizes the realms of the living, humans included. And in a language where the decorative is not about decoration, forms, materials, and figures are more polymorphous than identified by typology or periodic classification. Though everything pulses with life, it is within these nebulous exchanges — from carpets of hair to embroidered frames, from the delicate surface of an over-soaked, curling sheet of paper to baroque pearl necklaces hanging over landscapes — that Camille Fischer’s atmospheric installations exist as moments, qualities of a mythological present made of shifting icons: stained, sullied, withered. Feral, transdimensional worlds under the opalescence of stories yet to come.

Mathieu Buard

Following your exhibition at Maïa Muller, Oh Violette or the Politeness of Plants, I was particularly struck by your ornamental approach — both in its literary dimension, notably through your relationship to the poetic work of Lise Deharme, and in the presence of your pieces within multidisciplinary arrangements of intricate entanglements. Ornamental forms are everywhere, circulating in echo. Simply put: what is the importance of the flower for you, as a motif — or even as a subject?

Camille Fischer

I think it's the most common and obvious ornamental motif, and within the plant kingdom, it’s the most attractive — that’s its function: to be desirable, the thing that smells, that has the particularity of being colourful. Sometimes I wonder if our entire aesthetic sense rests solely on the flower. That maybe our idea of beauty comes entirely from it.

At one point, I began to think of the flower as a kind of transition between fauna and flora — because for flora to reproduce, it needs to attract fauna through colour and scent. So in that sense, it's almost a means of communication between the two kingdoms. Something that draws in and arouses.

Mathieu Buard

Like an interstice, a relational object between the two.

Camille Fischer

Yes, it’s a kiss. And maybe our earliest aesthetic rules, our sense of taste, of colour relationships, of proportion, all come from that repertoire, from there, from the flower. I sometimes ask myself: why do we find certain things beautiful? Maybe it all started, and was shaped, by flowers — or perhaps by the patterns of animal fur. That mythological sense of beauty. I’m fascinated by the Appaloosa, those horses with irregular spots.

Mathieu Buard

That floral or animal pattern is, at first glance, a powerful visual motif — a plastic sign. We instinctively perceive it as a form of beauty. Yet you transform these flowers; they’re never shown in their prime or in a moment of full bloom — not an epiphany, but rather in the hour of their decline.

Camille Fischer

Yes, it's that tipping point, the one that leans toward the end, that interests me. It’s very connected to my current state of mind, this feeling that we're living through a decline, the end of something. Like the Egyptians?

Mathieu Buard

The end of a civilisation?

Camille Fischer

Yes — even if it sounds heavy, I feel it more like a sunset, a twilight, a moment before nightfall. And what remains, that faint shimmer, is the flicker of hope wavering. The flowers I draw are no longer radiant, but possess a soft, muted beauty. Dusty colours that no longer fully reveal themselves. I love that fin-de-siècle symbolism — the softness of shaded, faded, powdery tones. The sublime in decline and withering. It’s another motif for me. And always the need to dodge the morbid!

There’s also something in the fact that these are colours that resist printing, in-between shades, those that shift, bastard tones, rebellious hues, the ones that escape screen calibration and digital colour systems.

Mathieu Buard

Like in your Iris painting series — forms in transition, never fully illuminated.

Camille Fischer

Exactly. That state of transition fascinates me, because it reveals both the past and a possible future. Nothing is fixed — everything remains open. And the eye becomes a seeker, trying to grasp variation, mutation, the shift… That flicker, the fleeting light, the glint of jewels that mesmerises…

Mathieu Buard

Yes, you add shiny, reflective, almost cosmic elements to your paintings, glitter, iridescent binders, heightening that visual instability.

Camille Fischer

Yes, instability is also attractive — deeply alluring. Light draws the eye, and its variations fascinate. What fascinates should never fully reveal itself. When you give everything right away, there’s nothing left to escape, and it extinguishes as much as it ignites. The kind of seduction that interests me is subtle, delicate, without excess — not the kind that overwhelms or imposes, leaving no room for the other to wander. Like the colours I use — tawny, powdery, stained pinks.

Mathieu Buard

Weak signals, almost invisible ones?

Camille Fischer

Exactly. But also, the seducer is almost a vulnerable being — in a position of weakness, of decline even. It means that the one being seduced has to be alert. It’s not about predation, but about fragile seduction made of soft pulses and fleeting glimmers.

Mathieu Buard

You feel that too in your landscapes — those exotic, extraterrestrial pastoral gardens, filled with discreet eroticism and an unusual atmosphere.

Camille Fischer

Yes, that’s tied to fantasy as well — to those distortions, like distant or unknown plants I paint. These parallel flowers speak to a form of orientalism, maybe, but also to the supposed impurity of that eroticism. There’s stain, pollen, the underside of lips, the complicity of miasmas. These landscapes seduce because they avoid the authoritative form of academicism — they remain accessible assemblages, vaporous, fragile apparitions with no borders or frames. Maybe a door or a gate appears, lost somewhere… But there must always be a way to escape.

Mathieu Buard

That fragility is present in your technique too.

Camille Fischer

Yes, my materials — paper, pastel — are incredibly delicate, almost ephemeral, like the wing of a butterfly, a grasshopper. That echoes the fragile junctions in flowers — like wilting tulip petals turned translucent, held by a thread. That tipping point, that precarity, where caramel or honey shades appear, really moves me. My papers degrade, they yellow, the pastel fades... There’s a deliberate ephemerality. Even when I flip through my works to compose wall pieces, the paper cracks, audibly. It’s also, I think, about accepting to take blows.

Mathieu Buard

And the irises — poisonous or twilight-toned — that you draw, can you speak about them?

Camille Fischer

I adore irises for their mystery. They’re full of secrets — their interior, their pistil, their velvety, fuzzy petals, their powdery scent both old and fresh, extremely refined — something between an old lady and an androgyne. A flower made of contradiction. Their colours are pastel, muddied, close to oyster tones, to veiled light — never contrasted, except in fleeting flashes. The iris, in terms of colour, is like looking through opalescent clouds. In a suave, non-macabre decadence.

Mathieu Buard

You often hang them like portraits, side by side… Is that also why you associate them with faces? Are they characters to you, like in a cabinet of curiosities?

Camille Fischer

Yes, to give them the status of a character. The iris has something of a baroque persona. Like those Italian soldiers with ostrich feathers on their heads — a plume, a panache. It transforms the flower into a portrait, and by associating it with painted faces, it becomes a kind of empowerment — as though the flower becomes an adornment. It’s also a way to strip the flower of its decorative connotation: the face brings the idea of portraiture to the flower.

And I never draw from an image of an iris. It’s more like a plastic synthesis. I don’t create portraits from reference — the face emerges through the ink’s wanderings on paper. It’s almost pareidolia, a recognition that comes after the fact.

Mathieu Buard

Yes, like the Chinese curio or the studiolo, where one gazes at selected marvels and projects oneself into them. Does your arrangement of drawings, juxtaposed, layered, become a kind of shifting atlas? Like a bouquet? As in textile design, where the pattern moves?

Camille Fischer

Yes, I compose like a melody, without fixed meaning. These are notes, offbeat, never perfectly aligned — they fall between beats. There are no closed series of flowers, but a vast whole that can be composed and recomposed according to the space, even the mood or climate, in a consciously musical rhythm — always rearranged against the grain. A kind of dandyism, with its unruly nature. A misplaced preciousness too. Opposed to the “perfect” flower, I’m interested in the withered one. It’s a kind of escape from dominant, bourgeois values once again. It’s no longer efficient. It’s also a relation to dream and to freedom, a sideways gaze. Fluidity softens the point of view. And so the forms and materials too, embroidery, pearls, textiles, patterns, all that grammar can always be recomposed.

Irregular pearl jewellery, delicate, almost unfinished embroidery — revealing the fragility, the reverse of things, the exposed thread... I like that the paper can be touched, rubbed, simply pinned. That transparency allows me to impress my fantasies without ever fully fixing them.

Mathieu Buard

How do you bring your compositions to an end, like your recent wallpaper piece? Do these large ensembles become paintings, still lifes, installations?

Camille Fischer

Out of necessity — because of deadlines. Otherwise, I could go on indefinitely. They're snapshots of a continuous flow, always reconfigurable. I like the idea of thinking of these compositions as a 360° bouquet, with no beginning or end. A potential landscape, like the remnants of a film set where anything could still happen — something you can walk around, where things aren’t neatly arranged. I don’t like single readings. Like textile motifs, I organize these multiple dimensions in a way that avoids the flatness or frontality that bores me. It’s a kind of fragmented narrative — not linear, more of an atmosphere.

It has a lot to do with the spontaneity of a teenager’s bedroom, layered in music and plastered with posters.

Mathieu Buard

Your works evoke a constellation — a claimed rococo spirit? Or a form of subtle counterculture?

Camille Fischer

Exactly. I like that confusion, that profusion — forms that escape classical order. It’s not efficient, it’s more theatrical. It creates something androgynous, or hermaphroditic — between states. I love the rococo, like the iris, for that bouncing complexity. Or taking what’s seen as tacky and sublimating it. A sort of beautiful loser vibe, like Johnny Thunders. I reject authoritarian modern aesthetics — the standard of newness, of calculated and cold normativity.

The spaces and installations I create, while evoking a palace or a bedroom, are like rococo atmospheres designed for pleasure, for singular and domestic reverie, without the pressure of a self-image to uphold. It’s also about telling another story within the story — through a piece of jewelry, a garment, makeup… An extension of self, with temperatures, sounds… a threshold where the windows would be open and the scent of the park would drift in.

It’s a mood, something indefinable: a protective shell, open to the outside, full of softness and delicacy, soaked in fantasies and their discomforts too.

Mathieu Buard

In the end, all of this stems from a sensitivity where material qualities are central, as if you could see through every surface… a gesture of style.

Camille Fischer

Yes — and ones you can project your fantasies onto. These veils, these perceptible suspensions don’t cancel expression. They linger, like a transparent veil or vapor, a surface crossed, where dust and sweat mix. And yes, my touch is everywhere. They used to call me Dirty Fingers at art school because I always left my marks. Everything carries my fingerprints.

Smoked Garden

On the material fragility of opiates from elsewhere, gathered into a bouquet.

More than a wunderkammer or a cabinet of appearance cultures, the grand garden Camille Fischer composes shelters, from beds to borders, the variations of adorned beings, whose garments are identity made portrait, skin itself,” says Antoine Lavoisier from beyond the grave.

“And in this great cosmic bath, both potential and brimming with vitality, where what remains is the matter of what is to come, everything blooms and vice versa” he continues inwardly, not displeased with the positive synthesis he has just produced on the multidisciplinary practice of the artist he observes from his patch of intangible clouds. Indeed, in the in-between of a dreamed Rococo salon or the bedroom of the eternally adolescent collector, Camille Fischer’s ornamental system embraces every medium and blends them all together. A crepuscular theater, where each represented fragment reveals the fragile and supreme fruit of flora — the flower. Her gesture, in its broadest sense, explores thes

e interconnections: both assembler and ornamentist, Camille reorganizes the realms of the living, humans included. And in a language where the decorative is not about decoration, forms, materials, and figures are more polymorphous than identified by typology or periodic classification. Though everything pulses with life, it is within these nebulous exchanges — from carpets of hair to embroidered frames, from the delicate surface of an over-soaked, curling sheet of paper to baroque pearl necklaces hanging over landscapes — that Camille Fischer’s atmospheric installations exist as moments, qualities of a mythological present made of shifting icons: stained, sullied, withered. Feral, transdimensional worlds under the opalescence of stories yet to come.

Mathieu Buard

Following your exhibition at Maïa Muller, Oh Violette or the Politeness of Plants, I was particularly struck by your ornamental approach — both in its literary dimension, notably through your relationship to the poetic work of Lise Deharme, and in the presence of your pieces within multidisciplinary arrangements of intricate entanglements. Ornamental forms are everywhere, circulating in echo. Simply put: what is the importance of the flower for you, as a motif — or even as a subject?

Camille Fischer

I think it's the most common and obvious ornamental motif, and within the plant kingdom, it’s the most attractive — that’s its function: to be desirable, the thing that smells, that has the particularity of being colourful. Sometimes I wonder if our entire aesthetic sense rests solely on the flower. That maybe our idea of beauty comes entirely from it.

At one point, I began to think of the flower as a kind of transition between fauna and flora — because for flora to reproduce, it needs to attract fauna through colour and scent. So in that sense, it's almost a means of communication between the two kingdoms. Something that draws in and arouses.

Mathieu Buard

Like an interstice, a relational object between the two.

Camille Fischer

Yes, it’s a kiss. And maybe our earliest aesthetic rules, our sense of taste, of colour relationships, of proportion, all come from that repertoire, from there, from the flower. I sometimes ask myself: why do we find certain things beautiful? Maybe it all started, and was shaped, by flowers — or perhaps by the patterns of animal fur. That mythological sense of beauty. I’m fascinated by the Appaloosa, those horses with irregular spots.

Mathieu Buard

That floral or animal pattern is, at first glance, a powerful visual motif — a plastic sign. We instinctively perceive it as a form of beauty. Yet you transform these flowers; they’re never shown in their prime or in a moment of full bloom — not an epiphany, but rather in the hour of their decline.

Camille Fischer

Yes, it's that tipping point, the one that leans toward the end, that interests me. It’s very connected to my current state of mind, this feeling that we're living through a decline, the end of something. Like the Egyptians?

Mathieu Buard

The end of a civilisation?

Camille Fischer

Yes — even if it sounds heavy, I feel it more like a sunset, a twilight, a moment before nightfall. And what remains, that faint shimmer, is the flicker of hope wavering. The flowers I draw are no longer radiant, but possess a soft, muted beauty. Dusty colours that no longer fully reveal themselves. I love that fin-de-siècle symbolism — the softness of shaded, faded, powdery tones. The sublime in decline and withering. It’s another motif for me. And always the need to dodge the morbid!

There’s also something in the fact that these are colours that resist printing, in-between shades, those that shift, bastard tones, rebellious hues, the ones that escape screen calibration and digital colour systems.

Mathieu Buard

Like in your Iris painting series — forms in transition, never fully illuminated.

Camille Fischer

Exactly. That state of transition fascinates me, because it reveals both the past and a possible future. Nothing is fixed — everything remains open. And the eye becomes a seeker, trying to grasp variation, mutation, the shift… That flicker, the fleeting light, the glint of jewels that mesmerises…

Mathieu Buard

Yes, you add shiny, reflective, almost cosmic elements to your paintings, glitter, iridescent binders, heightening that visual instability.

Camille Fischer

Yes, instability is also attractive — deeply alluring. Light draws the eye, and its variations fascinate. What fascinates should never fully reveal itself. When you give everything right away, there’s nothing left to escape, and it extinguishes as much as it ignites. The kind of seduction that interests me is subtle, delicate, without excess — not the kind that overwhelms or imposes, leaving no room for the other to wander. Like the colours I use — tawny, powdery, stained pinks.

Mathieu Buard

Weak signals, almost invisible ones?

Camille Fischer

Exactly. But also, the seducer is almost a vulnerable being — in a position of weakness, of decline even. It means that the one being seduced has to be alert. It’s not about predation, but about fragile seduction made of soft pulses and fleeting glimmers.

Mathieu Buard

You feel that too in your landscapes — those exotic, extraterrestrial pastoral gardens, filled with discreet eroticism and an unusual atmosphere.

Camille Fischer

Yes, that’s tied to fantasy as well — to those distortions, like distant or unknown plants I paint. These parallel flowers speak to a form of orientalism, maybe, but also to the supposed impurity of that eroticism. There’s stain, pollen, the underside of lips, the complicity of miasmas. These landscapes seduce because they avoid the authoritative form of academicism — they remain accessible assemblages, vaporous, fragile apparitions with no borders or frames. Maybe a door or a gate appears, lost somewhere… But there must always be a way to escape.

Mathieu Buard

That fragility is present in your technique too.

Camille Fischer

Yes, my materials — paper, pastel — are incredibly delicate, almost ephemeral, like the wing of a butterfly, a grasshopper. That echoes the fragile junctions in flowers — like wilting tulip petals turned translucent, held by a thread. That tipping point, that precarity, where caramel or honey shades appear, really moves me. My papers degrade, they yellow, the pastel fades... There’s a deliberate ephemerality. Even when I flip through my works to compose wall pieces, the paper cracks, audibly. It’s also, I think, about accepting to take blows.

Mathieu Buard

And the irises — poisonous or twilight-toned — that you draw, can you speak about them?

Camille Fischer

I adore irises for their mystery. They’re full of secrets — their interior, their pistil, their velvety, fuzzy petals, their powdery scent both old and fresh, extremely refined — something between an old lady and an androgyne. A flower made of contradiction. Their colours are pastel, muddied, close to oyster tones, to veiled light — never contrasted, except in fleeting flashes. The iris, in terms of colour, is like looking through opalescent clouds. In a suave, non-macabre decadence.

Mathieu Buard

You often hang them like portraits, side by side… Is that also why you associate them with faces? Are they characters to you, like in a cabinet of curiosities?

Camille Fischer

Yes, to give them the status of a character. The iris has something of a baroque persona. Like those Italian soldiers with ostrich feathers on their heads — a plume, a panache. It transforms the flower into a portrait, and by associating it with painted faces, it becomes a kind of empowerment — as though the flower becomes an adornment. It’s also a way to strip the flower of its decorative connotation: the face brings the idea of portraiture to the flower.

And I never draw from an image of an iris. It’s more like a plastic synthesis. I don’t create portraits from reference — the face emerges through the ink’s wanderings on paper. It’s almost pareidolia, a recognition that comes after the fact.

Mathieu Buard

Yes, like the Chinese curio or the studiolo, where one gazes at selected marvels and projects oneself into them. Does your arrangement of drawings, juxtaposed, layered, become a kind of shifting atlas? Like a bouquet? As in textile design, where the pattern moves?

Camille Fischer

Yes, I compose like a melody, without fixed meaning. These are notes, offbeat, never perfectly aligned — they fall between beats. There are no closed series of flowers, but a vast whole that can be composed and recomposed according to the space, even the mood or climate, in a consciously musical rhythm — always rearranged against the grain. A kind of dandyism, with its unruly nature. A misplaced preciousness too. Opposed to the “perfect” flower, I’m interested in the withered one. It’s a kind of escape from dominant, bourgeois values once again. It’s no longer efficient. It’s also a relation to dream and to freedom, a sideways gaze. Fluidity softens the point of view. And so the forms and materials too, embroidery, pearls, textiles, patterns, all that grammar can always be recomposed.

Irregular pearl jewellery, delicate, almost unfinished embroidery — revealing the fragility, the reverse of things, the exposed thread... I like that the paper can be touched, rubbed, simply pinned. That transparency allows me to impress my fantasies without ever fully fixing them.

Mathieu Buard

How do you bring your compositions to an end, like your recent wallpaper piece? Do these large ensembles become paintings, still lifes, installations?

Camille Fischer

Out of necessity — because of deadlines. Otherwise, I could go on indefinitely. They're snapshots of a continuous flow, always reconfigurable. I like the idea of thinking of these compositions as a 360° bouquet, with no beginning or end. A potential landscape, like the remnants of a film set where anything could still happen — something you can walk around, where things aren’t neatly arranged. I don’t like single readings. Like textile motifs, I organize these multiple dimensions in a way that avoids the flatness or frontality that bores me. It’s a kind of fragmented narrative — not linear, more of an atmosphere.

It has a lot to do with the spontaneity of a teenager’s bedroom, layered in music and plastered with posters.

Mathieu Buard

Your works evoke a constellation — a claimed rococo spirit? Or a form of subtle counterculture?

Camille Fischer

Exactly. I like that confusion, that profusion — forms that escape classical order. It’s not efficient, it’s more theatrical. It creates something androgynous, or hermaphroditic — between states. I love the rococo, like the iris, for that bouncing complexity. Or taking what’s seen as tacky and sublimating it. A sort of beautiful loser vibe, like Johnny Thunders. I reject authoritarian modern aesthetics — the standard of newness, of calculated and cold normativity.

The spaces and installations I create, while evoking a palace or a bedroom, are like rococo atmospheres designed for pleasure, for singular and domestic reverie, without the pressure of a self-image to uphold. It’s also about telling another story within the story — through a piece of jewelry, a garment, makeup… An extension of self, with temperatures, sounds… a threshold where the windows would be open and the scent of the park would drift in.

It’s a mood, something indefinable: a protective shell, open to the outside, full of softness and delicacy, soaked in fantasies and their discomforts too.

Mathieu Buard

In the end, all of this stems from a sensitivity where material qualities are central, as if you could see through every surface… a gesture of style.

Camille Fischer

Yes — and ones you can project your fantasies onto. These veils, these perceptible suspensions don’t cancel expression. They linger, like a transparent veil or vapor, a surface crossed, where dust and sweat mix. And yes, my touch is everywhere. They used to call me Dirty Fingers at art school because I always left my marks. Everything carries my fingerprints.