Hugo Ruyant

July 2025

Hugo Ruyant is a painter whose work sits at the crossroads of figurative narrative, material experimentation and fantasy, where everyday objects collide with ghostly apparitions to probe cultural myths and intimate emotions. His solo show, Air Conditioner Fantasies, opens at Galerie Michel Rein in Brussels on June 5 and runs through July 19, 2025.

Exhibition documentation Benjamin Baltus

Temple Magazine

The origin of the “Air Conditioner Fantasies” series and how it fits into your overall body of work?

Hugo Ruyant

This “Air Conditioner Fantasies” exhibition is my second solo show with Michel Rein gallery, and my first time exhibiting in Brussels as a painter. That made it emotionally huge for me. I studied at La Cambre, and over time I feel that’s where I really shaped my artistic identity—alongside the Brussels scene, which was pivotal for my development. I put a lot of (good) pressure on myself to impress friends who still work in Brussels, my artistic family there.

The stakes felt high, so I leaned into an experience from my South Korea residency last September. Lilia Medjeber (my partner) and I were in Gapyeong, a rural town near Seoul, living in a brutalist villa straight out of Parasite: ultra-modern, gorgeous, but isolated above a lake. We had to ration food—we weren’t motorized—so we’d get supplies for ten days. Just the two of us, in a hot, humid jungle, with venomous spiders roaming this massive villa.

A few days in, curator Julia visited. Around midnight, she called: “Hugo, can you come? I think someone broke in.” Immersed in this atmosphere of extreme capitalism mixed with superstition, I grabbed my phone’s torch and went to the dining room upstairs. I found Julia there, and a pungent smell hit me: alcohol, sweat, a vagabond’s stench. Spooked, I said, “Julia, want to sleep with us? Couch’s free. We’ll sort this out tomorrow.” By morning, we deduced it was just the air-conditioning malfunctioning in the downpour, releasing a pestilential odor.

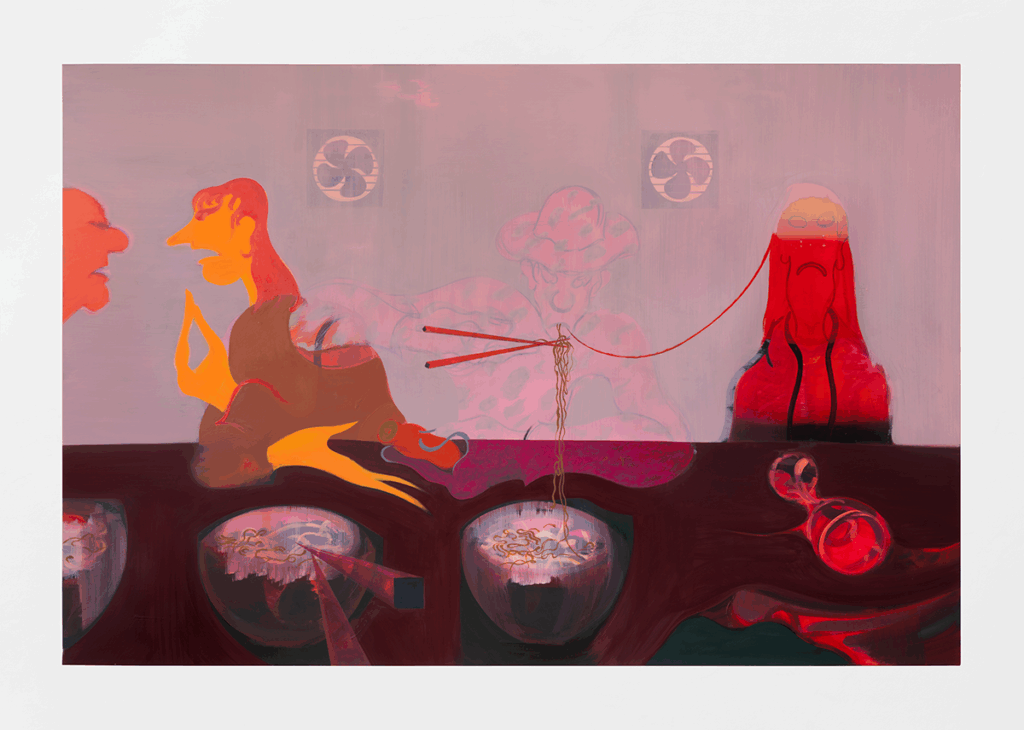

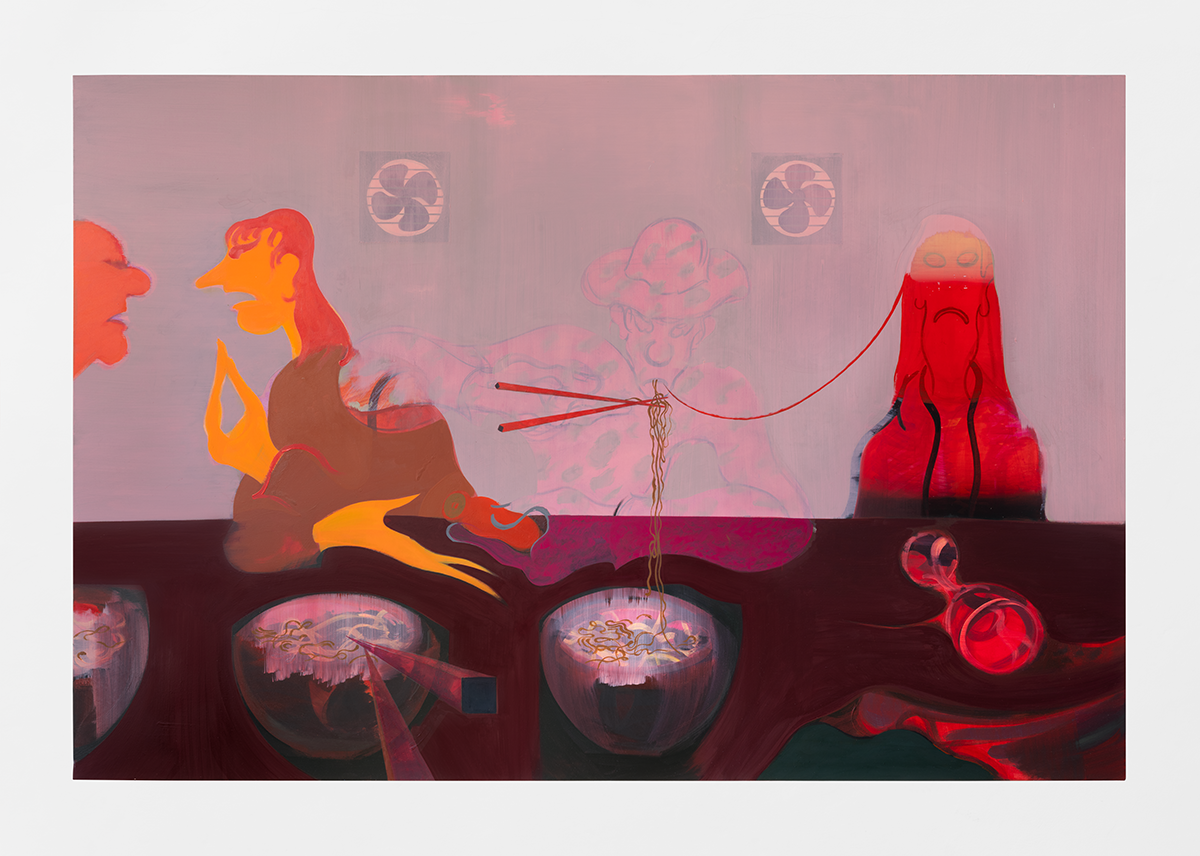

Back home, that scene became a fertile painting premise. I saw the chance to merge a ghostly figure with an AC unit—playing with a virtual character that might vanish behind the objects it operates. It felt like a conceptual mash-up: a common yet exotic object (the AC) with a stereotyped figure tied to Asian—and universal—ghost stories. That stuck with me: it gave me a transversal idea for a show that’s part plastic experiment, part cultural tale. I treated the exhibition almost like a storybook, making a detour into fantasy—whereas my other series often dissect grotesque social relations. Here, I pressed the “fantastic” button to craft a painterly journey around this ghost–AC union.

Temple Magazine

Since this narrative became the pretext for the series, it also mirrors your painting process. You keep covering and re-covering and redrawing—there’s an echo between the story and how you paint?

Hugo Ruyant

Absolutely. Whenever I pick a subject, I look for how the story or image relates to what happens physically when I paint. Here, the notion of covering up, common in painting, resonated with scenes where real objects interact with things that aren’t really there. I’m always thinking about painting itself, but this time I wanted something hyper-specific, stepping aside from usual political themes, consumption, power, to propose something precise, almost miniature.

That idea of covering was there from my early painting days, when I was still buried in material. Now I sought a flatter, surface-driven approach, almost poster-like. I used very shallow stretchers so the canvases sit close to the wall, evoking the teen posters we all had. I aimed for a painting that feels like printed imagery: neither heavily impastoed nor perfectly smooth, but with a decisive, economical execution. This efficient surface interplay meant less texture than in my other works, but it was an aesthetic pleasure—like flipping through pages of a book.

Temple Magazine

Whether it’s for this show or earlier work, you blend different graphic worlds and often mix complementary visual registers. That comes from your cartoon and print-image background?

Hugo Ruyant

Yes. I came up through comics, DIY fanzines and print imagery, so I’ve always had an appetite for a wide visual spectrum—from drawing to photography. In my painting I deliberately mix registers: some areas are razor-sharp and obvious, while others are more layered and unsettled. Conceptually it feels almost like sculpture or collage, but executed with paint.

My touchstones aren’t strictly fine-art—they’re experimental cartoonists like Christopher Forgues (CF) and his POWR MASTRS books, which feel as much like painting as comic pages. I’m drawn to lines that cut straight through the world—think clear-line Tintin panels that give equal weight to character and mountain. Lately I’ve also been inspired by painting’s raw energy in James Ensor’s work or Magritte’s “vache” period—brash, even ugly, yet fiercely abstract. I aim to land right between those extremes.

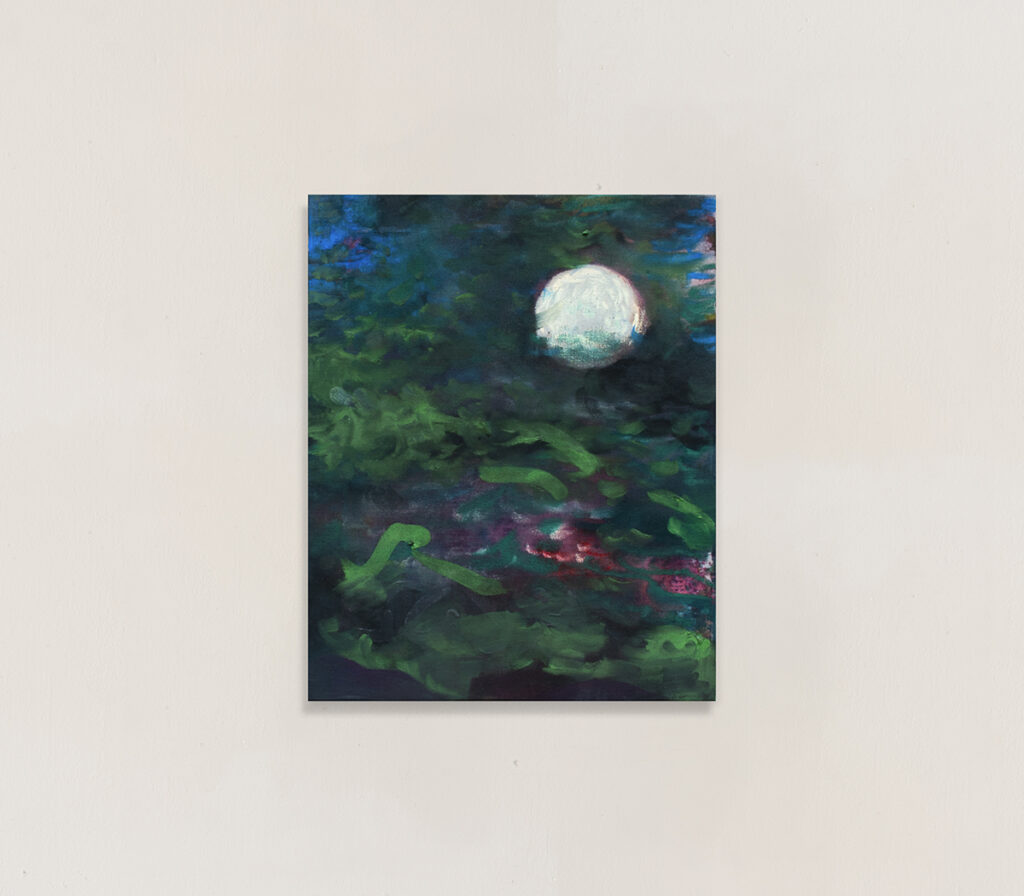

I always start from drawing: I seek an economy and lift in the line. I love observational sketching, it’s pure pleasure and generosity, yet so far my big canvases come from invented ideas, not direct observation. One day, once I’m less fearful, I’d like to integrate those studio drawings into my paintings. For now, painting itself is my challenge and growth zone—an arena where I confront my fears. Hopefully, down the road, I’ll even let myself tackle subjects that feel “classic” or “cheesy,” like a sunset, things I secretly long to paint.

I think artists sometimes layer concepts to hide a very simple, human desire, to capture pure emotion. Drawing and painting have that primal power, like music, to move you directly through color. That tension—intimidating yet thrilling—is exactly why I keep painting.

Temple Magazine

How do you approach your color choices? Do you work in color series, or is it more a personal palette that resurfaces?

Hugo Ruyant

Color is probably the main reason I paint—my poetic playground. I treat it almost independently from subject. In the “Air Conditioner Fantasy” title piece, I floated a deep aubergine backlight above the scene, split the canvas with two reds, and even made the fans into flowers. I trust my gut in the moment. I also love the surreal color shifts in Lucky Luke—blue foreground, yellow background—that shock and enliven the image. For me, it’s about creating musicality above narrative.

Temple Magazine

Your use of perspective, compartmentalizing elements as if through a wide-angle lens, does that stem from photographic techniques?

Hugo Ruyant

Not directly. My distortions come from drawing, from a willingness to let space stretch and fold. I do look at photography—especially for abstract qualities—but I’m more driven by the comic-book urge to give every corner of the scene equal life. In “Air Conditioner Fantasy,” I pushed the moldings forward with extreme perspective, deliberately a bit vulgar, almost like a spear jabbing into the viewer. It’s playful, immersive, even if it’s a bit outrageous. That’s the fun of it.

Temple Magazine

You could even spot that same thing in some kitschy paintings?

Hugo Ruyant

Definitely. There’s something touching in how my figures look cramped against the edge of the canvas—almost clumsy, like they’re stumbling into the frame. That slight awkwardness feels genuine and human.

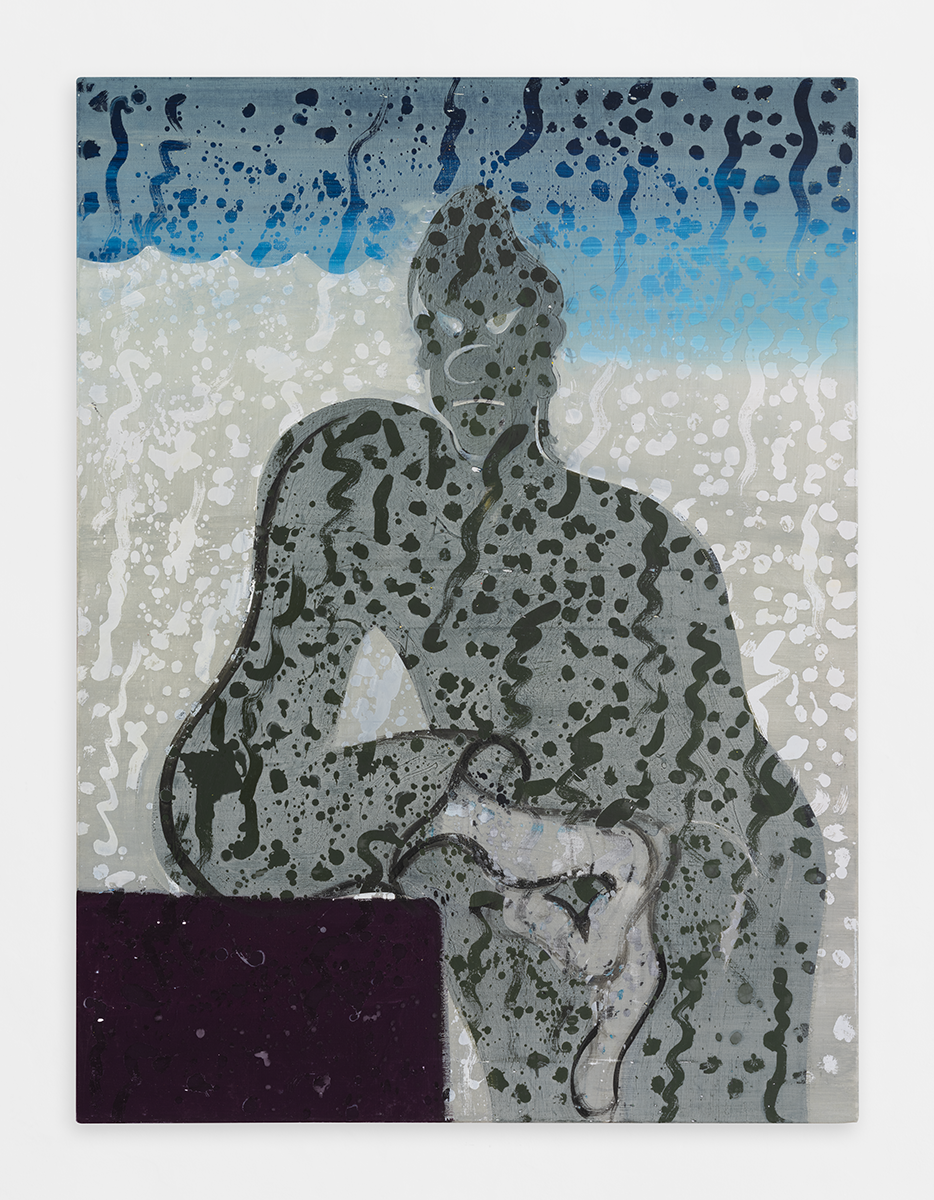

It’s really about rhythm rather than continuity. I don’t want to cram the entire story into a single painting. I try to make each piece read instantly, like a comic panel: a brief glimpse of desire or emotion. In this show, most works are muted, night-drenched scenes that carry a hushed tension—then “Forever” hits you with daylight and brightness, like a flashback to that Korean nightmare. To me, it’s about sequencing: a silent series of paintings punctuated by one sudden burst of light, creating a kind of narrative relief from one canvas to the next.

Temple Magazine

The origin of the “Air Conditioner Fantasies” series and how it fits into your overall body of work?

Hugo Ruyant

This “Air Conditioner Fantasies” exhibition is my second solo show with Michel Rein gallery, and my first time exhibiting in Brussels as a painter. That made it emotionally huge for me. I studied at La Cambre, and over time I feel that’s where I really shaped my artistic identity—alongside the Brussels scene, which was pivotal for my development. I put a lot of (good) pressure on myself to impress friends who still work in Brussels, my artistic family there.

The stakes felt high, so I leaned into an experience from my South Korea residency last September. Lilia Medjeber (my partner) and I were in Gapyeong, a rural town near Seoul, living in a brutalist villa straight out of Parasite: ultra-modern, gorgeous, but isolated above a lake. We had to ration food—we weren’t motorized—so we’d get supplies for ten days. Just the two of us, in a hot, humid jungle, with venomous spiders roaming this massive villa.

A few days in, curator Julia visited. Around midnight, she called: “Hugo, can you come? I think someone broke in.” Immersed in this atmosphere of extreme capitalism mixed with superstition, I grabbed my phone’s torch and went to the dining room upstairs. I found Julia there, and a pungent smell hit me: alcohol, sweat, a vagabond’s stench. Spooked, I said, “Julia, want to sleep with us? Couch’s free. We’ll sort this out tomorrow.” By morning, we deduced it was just the air-conditioning malfunctioning in the downpour, releasing a pestilential odor.

Back home, that scene became a fertile painting premise. I saw the chance to merge a ghostly figure with an AC unit—playing with a virtual character that might vanish behind the objects it operates. It felt like a conceptual mash-up: a common yet exotic object (the AC) with a stereotyped figure tied to Asian—and universal—ghost stories. That stuck with me: it gave me a transversal idea for a show that’s part plastic experiment, part cultural tale. I treated the exhibition almost like a storybook, making a detour into fantasy—whereas my other series often dissect grotesque social relations. Here, I pressed the “fantastic” button to craft a painterly journey around this ghost–AC union.

Temple Magazine

Since this narrative became the pretext for the series, it also mirrors your painting process. You keep covering and re-covering and redrawing—there’s an echo between the story and how you paint?

Hugo Ruyant

Absolutely. Whenever I pick a subject, I look for how the story or image relates to what happens physically when I paint. Here, the notion of covering up, common in painting, resonated with scenes where real objects interact with things that aren’t really there. I’m always thinking about painting itself, but this time I wanted something hyper-specific, stepping aside from usual political themes, consumption, power, to propose something precise, almost miniature.

That idea of covering was there from my early painting days, when I was still buried in material. Now I sought a flatter, surface-driven approach, almost poster-like. I used very shallow stretchers so the canvases sit close to the wall, evoking the teen posters we all had. I aimed for a painting that feels like printed imagery: neither heavily impastoed nor perfectly smooth, but with a decisive, economical execution. This efficient surface interplay meant less texture than in my other works, but it was an aesthetic pleasure—like flipping through pages of a book.

Temple Magazine

Whether it’s for this show or earlier work, you blend different graphic worlds and often mix complementary visual registers. That comes from your cartoon and print-image background?

Hugo Ruyant

Yes. I came up through comics, DIY fanzines and print imagery, so I’ve always had an appetite for a wide visual spectrum—from drawing to photography. In my painting I deliberately mix registers: some areas are razor-sharp and obvious, while others are more layered and unsettled. Conceptually it feels almost like sculpture or collage, but executed with paint.

My touchstones aren’t strictly fine-art—they’re experimental cartoonists like Christopher Forgues (CF) and his POWR MASTRS books, which feel as much like painting as comic pages. I’m drawn to lines that cut straight through the world—think clear-line Tintin panels that give equal weight to character and mountain. Lately I’ve also been inspired by painting’s raw energy in James Ensor’s work or Magritte’s “vache” period—brash, even ugly, yet fiercely abstract. I aim to land right between those extremes.

I always start from drawing: I seek an economy and lift in the line. I love observational sketching, it’s pure pleasure and generosity, yet so far my big canvases come from invented ideas, not direct observation. One day, once I’m less fearful, I’d like to integrate those studio drawings into my paintings. For now, painting itself is my challenge and growth zone—an arena where I confront my fears. Hopefully, down the road, I’ll even let myself tackle subjects that feel “classic” or “cheesy,” like a sunset, things I secretly long to paint.

I think artists sometimes layer concepts to hide a very simple, human desire, to capture pure emotion. Drawing and painting have that primal power, like music, to move you directly through color. That tension—intimidating yet thrilling—is exactly why I keep painting.

Temple Magazine

How do you approach your color choices? Do you work in color series, or is it more a personal palette that resurfaces?

Hugo Ruyant

Color is probably the main reason I paint—my poetic playground. I treat it almost independently from subject. In the “Air Conditioner Fantasy” title piece, I floated a deep aubergine backlight above the scene, split the canvas with two reds, and even made the fans into flowers. I trust my gut in the moment. I also love the surreal color shifts in Lucky Luke—blue foreground, yellow background—that shock and enliven the image. For me, it’s about creating musicality above narrative.

Temple Magazine

Your use of perspective, compartmentalizing elements as if through a wide-angle lens, does that stem from photographic techniques?

Hugo Ruyant

Not directly. My distortions come from drawing, from a willingness to let space stretch and fold. I do look at photography—especially for abstract qualities—but I’m more driven by the comic-book urge to give every corner of the scene equal life. In “Air Conditioner Fantasy,” I pushed the moldings forward with extreme perspective, deliberately a bit vulgar, almost like a spear jabbing into the viewer. It’s playful, immersive, even if it’s a bit outrageous. That’s the fun of it.

Temple Magazine

You could even spot that same thing in some kitschy paintings?

Hugo Ruyant

Definitely. There’s something touching in how my figures look cramped against the edge of the canvas—almost clumsy, like they’re stumbling into the frame. That slight awkwardness feels genuine and human.

It’s really about rhythm rather than continuity. I don’t want to cram the entire story into a single painting. I try to make each piece read instantly, like a comic panel: a brief glimpse of desire or emotion. In this show, most works are muted, night-drenched scenes that carry a hushed tension—then “Forever” hits you with daylight and brightness, like a flashback to that Korean nightmare. To me, it’s about sequencing: a silent series of paintings punctuated by one sudden burst of light, creating a kind of narrative relief from one canvas to the next.