Le Châ

August 2025

Le Châ, a UFO from the depths of the ages, questions time, the lines of desire and weightlessness. Emerging from the underground galaxy, she sings her laments as she wanders, speaking to humans about their relationship to the world. Cat-folk music, baroque and drone, the use of esotericism, she arrives.

Temple Magazine

How did the character of Le Châ come about? Was it first the instrument that triggered all this?

Lutèce Lockness

It was a crossroads of circumstances. I was still fumbling around, and honestly it could have lasted a long time… with the scheduled date approaching I had to find the solutions to get out of my fears. The first song begins with a thought of medieval illuminations. With my flash of being a cat, to better endure certain situations in daily life, the Irish bouzouki I had at hand, an instrument shaped like a tear, the medieval imaginary appeared directly. I saw an illumination. The timid serenade at the beginning of my first piece came like a natural confidence.

This first track begins very softly, a sensitive, harmless caress. It is this cat rubbing against legs and chair feet. Then it advances and bares its teeth, it shows its claws. The pure, delicate tears of the beginning turn into splatters of blood. It stains. “You thought it would be this, well look at that.” That is what this song says. It is also a tunnel shaped like a funnel, at the beginning there is light and landscape but then it narrows towards a black hole without gravity.

Since there is something medieval in the notes of the opening nursery rhyme, I needed to move time into the present-future, and shift the intention to make the sound creak. I imagined that by playing, Le Châ then calls forth other temporalities. I had to invite the future, even if it is retro. Spaceships come join us at the party, with inside them pasts, presents, imperfects and pluperfects. I also imagined that while singing a plane flies through the sky and Le Châ grabs it with her hand to look at it. The plane is tiny, perspectives do not exist, we are in a Flemish painting, and the small becomes the large and the large, the small. No more scale between elements. Abolition. At the end of the song, a plucked guitar brings in the rising rhythm, and for Le Châ it is a climb into trance. It is her dose. The guitar of my friend Christoph Fink comes rumbling like a black cloud filled with electricity that threatens and changes the air that contaminates us. We become nothing but electricity.

Now I know what this first song tells without significant words. It is the garrigue, magnificent, teeming with thorns, that bursts into flames and turns into chaos. Despite human mechanical attempts like Canadairs pouring sea water onto the fire, everything burns. And the insects die. The pines char. The stars disappear, too much smoke, the earth cracks, the stones become meteorites and Le Châ cries blood.

Temple Magazine

Can you tell us about the origin of Le Châ and how it first appeared?

Lutèce Lockness

First composition of Le Châ: November 2023, I spent a month in Berlin, lost, I became the shadow of Nico, my German friend. I followed him everywhere. For his mother’s birthday, he took me to lunch at her place. There were her two childhood friends, they were old, they did not speak English, they did not speak French, and I did not speak German. We looked at each other, we smiled, we sniffed each other and we ate cherry pudding and then onion soup with cheese in porcelain bowls. Uncomfortable not knowing how to enter into communication, I clung to the idea of being a cat.

I then dozed off on the couch in the middle of the family gathering, the guests talking, we were there together, everything was fine. A month later, I had this old bouzouki that I was dragging around, just in case I could play it. I had snatched it to check if we had anything to say to each other, and now I had to sing a song in two weeks on a real stage. It was my dream, but also my mountain. And I had nothing. I thought about what I was going to tell in the song, to start writing, but that was not my way in for music. I could not do it. I did not know what to say to other humans, except that we are stupid and heading straight into the wall. I could not write lyrics for a song. My self-judged thoughts felt too “emo”, so I gave up on writing words to sing, I would have to enter through another door to discover my song.

And if I really wanted to say what was in my heart to humans, it was better to be something other than human. I built the costume with Juliette, who had just given birth. With her baby at her breast she sewed day and night to get me ready to step on stage. I would be this Châ, sad and angry, meowing as it pleased with the winds.

Temple Magazine

So when Le Châ appeared, it was very spontaneous, or was it, as you said, more of a refuge, a mask that allowed you not to appear as Lutèce?

Lutèce Lockness

Being a creature allows me to free myself from many things: the projections people can have of me, my identity, or even my own demands. For example, being a young white woman comes with projections. Le Châ is free, it lets me avoid those stupid frameworks and focus on what matters: living intensely and singing it. It is true that there is a “mask”, but here it is a reversed mask, a mask turned inside out. I show my face. I do not hide. In fact, I reveal myself more deeply on stage.

This absurd cat brings me back to something profound inside me, something that cannot find its place in my citizenship. It is almost primal—a way of being alive that is not necessarily human. I let life move through me, and I let myself be guided by emotion through Le Châ. By putting on this skin, I move away from social, identity, and citizen constraints. I become a chimera, not clearly defined, and that frees me. And yes, Le Châ came out of necessity; I had to own myself in order to sing, and my shyness was taking over. I had to let out my monster, the one outside the codes. I thought of illuminations, the follies of the Middle Ages, ancient music, mystery, the Sphinx… I needed a non-human gaze, an observer. Out of all this, the cat appeared. Neither boy nor girl, neither good nor evil. I discover it as I embody it.

From the very first performance, I needed this costume. Even if I sang only once in my life, for that one time I had to have the costume, no matter the cost. It was vital, hiding to better show myself. Since then I have understood that this costume is a portal. It is not even really a cat anymore, in fact. It has become a chimera, a hybrid creature opening onto imagination. It allows me to embody strangeness, to explore another point of view, to push past the barrier of my own vision, to open up, to step aside in order to discover. Wider.

Temple Magazine

You also mentioned this invented language, this way of singing that frees you from literal meaning. How did it come about? Do you want to make it into a constructed language?

Lutèce Lockness

Not at all. It is not a language, well, it is the language of dreams. You should not look for words or sentences. In fact, I have been singing since I was a child. I learned by listening, by imitating. I have always sung in “yogurt,” in chat-rabia. Le Châ speaks this language. And it became a means of expression.

It allows me to focus on something else entirely, instead of fixing the story of my song with words. That does not mean that each song does not have its own subject or precise story! But it is present in another way, not through words. I have recently told myself that my real instrument is my voice, my voice in my body. That is how I make music, not through words. At least for now.

Temple Magazine

How do you actually work? Do you record yourself? How does a song come to life for you?

Lutèce Lockness

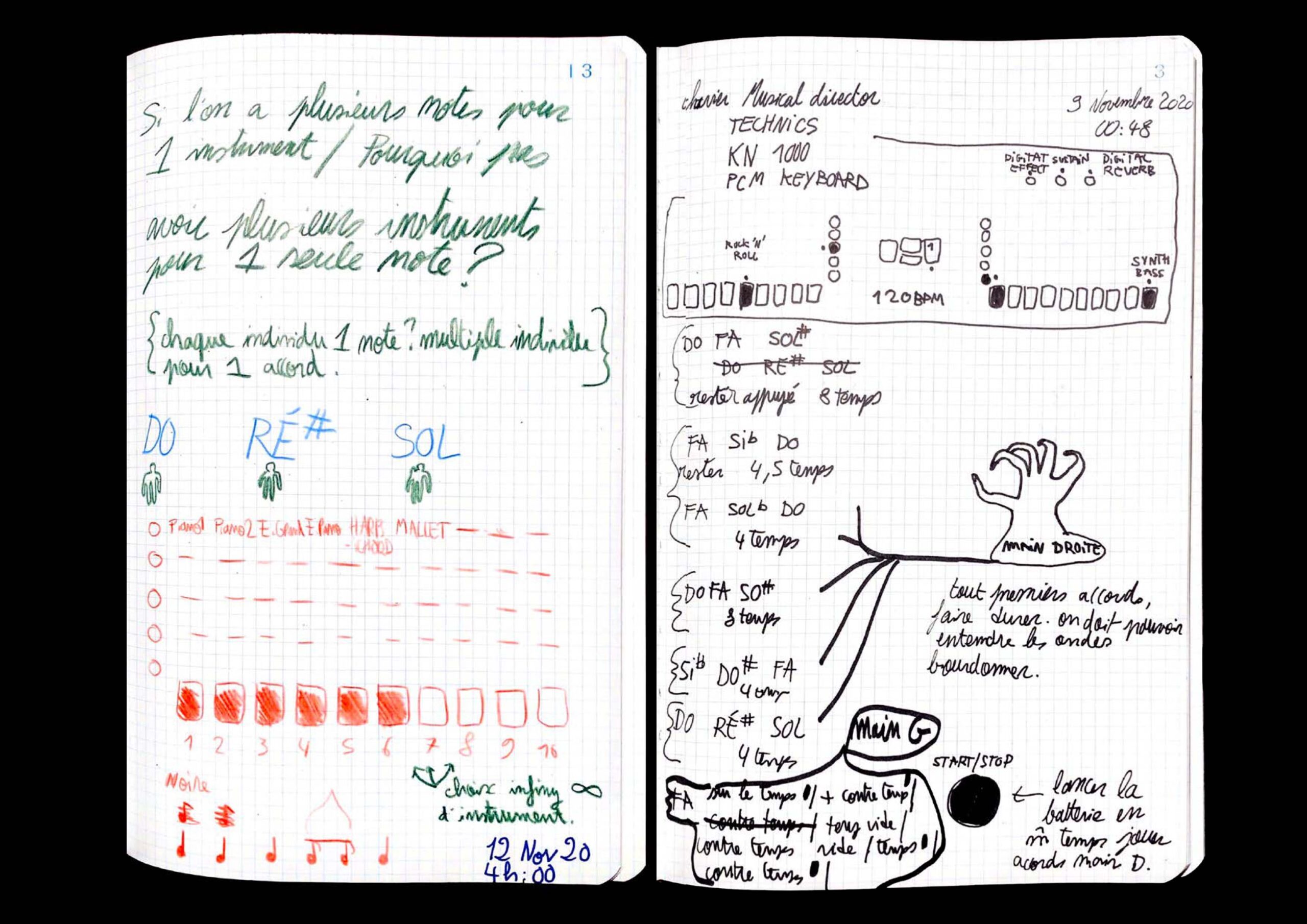

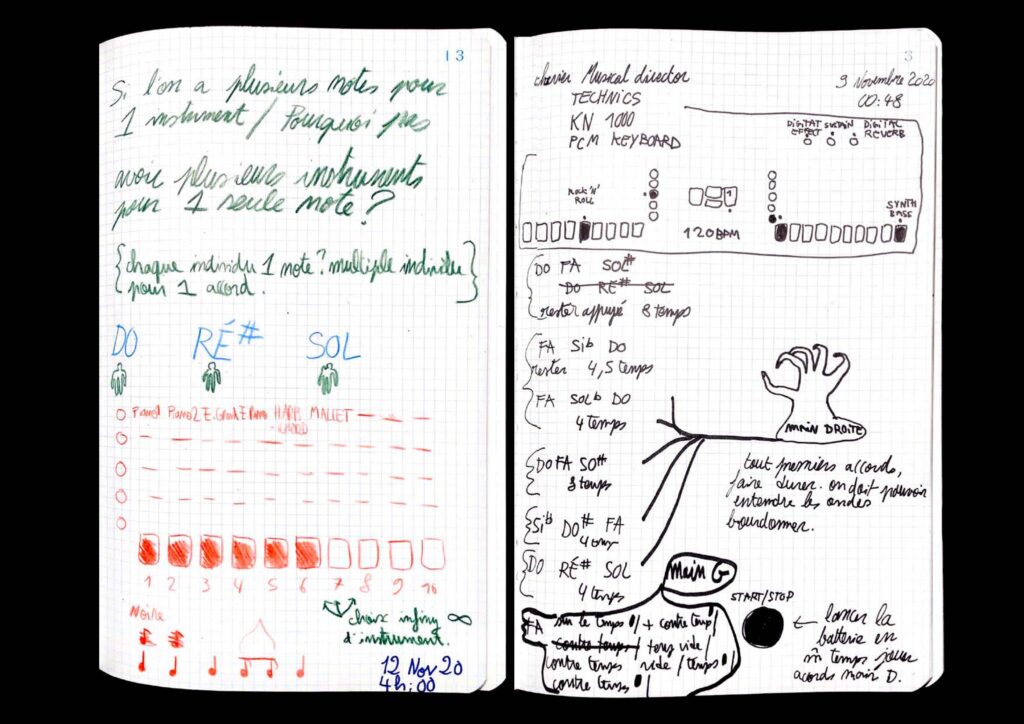

These are very intimate moments, often alone in my room, with very basic equipment. For the first song I had two microphones balancing inside my felt-tip box, I was at my desk and I closed my eyes. I played the bouzouki, I improvised, I searched for sequences of notes that touched me. When something resonated inside me, I recorded the sequence, I listened back, I searched for voices. I tried several voice options, several kinds of emotions, several scenarios in my head. Different characters. I experimented with the sounds of my voice, I discovered. I dug toward textures that creaked if it felt too obvious. At the same time I listened to a lot of music to soak myself in other things and to mix different worlds.

I also improvise a lot over music that is not mine, I jam with YouTube. It allows me to explore different scales, like training. And it comes back later, in my songs. I record myself constantly. Then I listen, sometimes I send the recordings to two or three close people who are good anchors for me. Or I keep them and rediscover them later, sometimes a year later. And then, with new eyes, with new musicality, I start something again from that. It is intuitive. It takes time and a song is made of multiple layers, temporal and emotional. It is not so separate from my life. It balances it. It is in tandem. I sing, I record, I go live, I come back, I listen, I cry, I sing again. Also I often compose while thinking of my next concert, I project myself into the space, it lights a fire inside me.

Temple Magazine

So on stage, a live performance can completely shift depending on your mood?

Lutèce Lockness

Well, yes and no. But that’s what I find crazy since I started performing, it’s only been a year. There’s such a gap between intimate creation and being on stage. They are two different jobs. Recording a song and playing it again is also a kind of time travel. But for me, each performance is a total unveiling. It’s very emotionally intense. Before and after, I’m shaken. A friend once told me it was “cat-seed”… because the cat plants seeds and sometimes it’s painful.

On stage, I don’t feel well and at the same time, it’s a feeling that touches the sublime, it’s extreme sport, a kind of parachute jump, but I always land on my feet. For now.

My goal is to express emotion, not to “sing well”—well, “singing well” is about being right, in the moment. What I sing is a direct translation of a feeling, but I am also an open score of the song’s story and its subject. Someone once told me I should “translate” what I sing, but I don’t want to. The translation is already there: it’s sonic, physical. It’s already a language in itself. Each song has its thread, its backdrop, its panel of vocal sounds and emotions, and on stage I have the space to weave with what is happening in the moment. So yes, there’s room for maneuver depending on the lived experience of the live performance, which allows each concert to adapt.

Temple Magazine

You also talk about journeys, exploration through listening. Are these journeys you’d like to make physically, or is it only through listening?

Lutèce Lockness

For now, I discover through listening. But I want to go discover high culture sounds. I’d like to go to Japan… in Asia, in Africa… in Mongolia! All these places I don’t know except through a screen or through music. I want to explore sonorities yes, instruments, traditional drums and see what it triggers, and play with that, cut and paste all that into new interwoven worlds. Not to integrate a style, but to feed the phonetic alphabet of Le Châ! The investigation is infinite.

Temple Magazine

You’re preparing an album, right? How are you approaching this step?

Lutèce Lockness

Yes, it’s the first time I’m doing this. And it’s yet another process, very different from composing alone in my room. What’s great is that I get along very well with the label team with whom we’re releasing the record “Le Châ.” Pan European allows me to have someone else besides me, invested in the release of the record. Without that, you feel very alone. It creates real support to move forward, to anchor, to accept the state of the sound, to have another ear.

Making a record feels like writing an epic.

At first, I wanted to re-record everything in the studio, “the proper way.” But Arthur from the label reminded me what Le Châ was. And finally, we decided to keep the raw recordings, born from my confidences in my room. The very first takes. The birth of the songs. At the moment when I was composing without thinking of an album, just letting things out in my intimate cocoon. And in fact, those versions, with wrong notes sometimes, a badly recorded bouzouki, carried such a true emotion that we wanted to keep them as a base. Afterwards, I rework them by adding layers. And in any case I had already built my live performances from these first drafts, later inviting other friends and artists to play on them, following very precise directions of Le Châ of course.

For the live shows, that’s already more or less how I do it: a very light first improvisation, just an intention or chords, and then I develop. I add sounds—frogs, spaceships, thunder— depending on the universe I project. I tell myself: “Where are we? Who am I singing for? For frogs? Okay, then we’re near a swamp.” I build a setting like a little film around each song. Sometimes it’s a Lynch film or a Miyazaki one. Other times, we’re under the full moon, in the mud, with creatures and insects. With fire. I also sing for the dead. And from there, I invite other musicians, I tell them about this world, the story of the song, even if it’s very open. I tell them, for example: “Here, I’d like to hear a kind of electricity in the air. Here’s a loop of the song where you could appear, if it speaks to you, play.” Or “Here are my notes and my emotion, listen to this.” And they answer me, I receive material, sometimes ten minutes of hurdy-gurdy drone, or an entire organ piece played by Jean Rondeau. Then I cut, and I recompose on top again. An exquisite corpse. It’s lacework, an assemblage of fragments and points of view.

Temple Magazine

And musical collaborations, that’s not a format you’ve experimented with live yet?

Lutèce Lockness

Not yet, but I’d like to. Now, while working on the tracks for the mix, I realize I want to move towards something more orchestral, wider, even freer live. For now I launch the backing track myself on stage and I play on top, but I dream of having jam moments live. With bases, of course. Because in my songs, there’s an orchestra accompanying me! One day they will all play around Le Châ on stage. That would be magnificent.

Inviting other musicians on stage would also shift the gaze a little, because I feel that for now, people are mostly looking at Le Châ. And that’s normal, the show is still short, it’s a real encounter with him. But Le Châ is just a door to imagination and music. It’s not the subject itself. It opens onto other worlds.

Temple Magazine

And for you, this character helped you move towards music.

Lutèce Lockness

Yes, it led me to music, but not only that. It also made me dream of images. I had never imagined making a film. I thought it was completely crazy, too complex. But with Le Châ, I want to propose visions, to explore image differently. It pushes me to work with visual artists, and to create together, the same way as with musicians. There are entire worlds to invent, to develop. And at the same time, there are already anchor points that Le Châ proposes. It allows ego to dissolve, to give rather than to take. It’s a call for collective creation — visual, musical, narrative. I feel like everything is still to be done, and that it’s infinite. It carries me.

Le Châ is not fixed. It’s a chimera, a password, a vehicle. I want to make it mutate: it can become a woman, or travel through time… It’s magical. It’s in permanent transformation. And that’s what I love.

Photos credits

@baptista.numero8

@igz_d8

@anjjacorh

@pierretopire

@pseudohugo

@margellea

Temple Magazine

Temple Magazine

How did the character of Le Châ come about? Was it first the instrument that triggered all this?

Lutèce Lockness

It was a crossroads of circumstances. I was still fumbling around, and honestly it could have lasted a long time… with the scheduled date approaching I had to find the solutions to get out of my fears. The first song begins with a thought of medieval illuminations. With my flash of being a cat, to better endure certain situations in daily life, the Irish bouzouki I had at hand, an instrument shaped like a tear, the medieval imaginary appeared directly. I saw an illumination. The timid serenade at the beginning of my first piece came like a natural confidence.

This first track begins very softly, a sensitive, harmless caress. It is this cat rubbing against legs and chair feet. Then it advances and bares its teeth, it shows its claws. The pure, delicate tears of the beginning turn into splatters of blood. It stains. “You thought it would be this, well look at that.” That is what this song says. It is also a tunnel shaped like a funnel, at the beginning there is light and landscape but then it narrows towards a black hole without gravity.

Since there is something medieval in the notes of the opening nursery rhyme, I needed to move time into the present-future, and shift the intention to make the sound creak. I imagined that by playing, Le Châ then calls forth other temporalities. I had to invite the future, even if it is retro. Spaceships come join us at the party, with inside them pasts, presents, imperfects and pluperfects. I also imagined that while singing a plane flies through the sky and Le Châ grabs it with her hand to look at it. The plane is tiny, perspectives do not exist, we are in a Flemish painting, and the small becomes the large and the large, the small. No more scale between elements. Abolition. At the end of the song, a plucked guitar brings in the rising rhythm, and for Le Châ it is a climb into trance. It is her dose. The guitar of my friend Christoph Fink comes rumbling like a black cloud filled with electricity that threatens and changes the air that contaminates us. We become nothing but electricity.

Now I know what this first song tells without significant words. It is the garrigue, magnificent, teeming with thorns, that bursts into flames and turns into chaos. Despite human mechanical attempts like Canadairs pouring sea water onto the fire, everything burns. And the insects die. The pines char. The stars disappear, too much smoke, the earth cracks, the stones become meteorites and Le Châ cries blood.

Temple Magazine

Can you tell us about the origin of Le Châ and how it first appeared?

Lutèce Lockness

First composition of Le Châ: November 2023, I spent a month in Berlin, lost, I became the shadow of Nico, my German friend. I followed him everywhere. For his mother’s birthday, he took me to lunch at her place. There were her two childhood friends, they were old, they did not speak English, they did not speak French, and I did not speak German. We looked at each other, we smiled, we sniffed each other and we ate cherry pudding and then onion soup with cheese in porcelain bowls. Uncomfortable not knowing how to enter into communication, I clung to the idea of being a cat.

I then dozed off on the couch in the middle of the family gathering, the guests talking, we were there together, everything was fine. A month later, I had this old bouzouki that I was dragging around, just in case I could play it. I had snatched it to check if we had anything to say to each other, and now I had to sing a song in two weeks on a real stage. It was my dream, but also my mountain. And I had nothing. I thought about what I was going to tell in the song, to start writing, but that was not my way in for music. I could not do it. I did not know what to say to other humans, except that we are stupid and heading straight into the wall. I could not write lyrics for a song. My self-judged thoughts felt too “emo”, so I gave up on writing words to sing, I would have to enter through another door to discover my song.

And if I really wanted to say what was in my heart to humans, it was better to be something other than human. I built the costume with Juliette, who had just given birth. With her baby at her breast she sewed day and night to get me ready to step on stage. I would be this Châ, sad and angry, meowing as it pleased with the winds.

Temple Magazine

So when Le Châ appeared, it was very spontaneous, or was it, as you said, more of a refuge, a mask that allowed you not to appear as Lutèce?

Lutèce Lockness

Being a creature allows me to free myself from many things: the projections people can have of me, my identity, or even my own demands. For example, being a young white woman comes with projections. Le Châ is free, it lets me avoid those stupid frameworks and focus on what matters: living intensely and singing it. It is true that there is a “mask”, but here it is a reversed mask, a mask turned inside out. I show my face. I do not hide. In fact, I reveal myself more deeply on stage.

This absurd cat brings me back to something profound inside me, something that cannot find its place in my citizenship. It is almost primal—a way of being alive that is not necessarily human. I let life move through me, and I let myself be guided by emotion through Le Châ. By putting on this skin, I move away from social, identity, and citizen constraints. I become a chimera, not clearly defined, and that frees me. And yes, Le Châ came out of necessity; I had to own myself in order to sing, and my shyness was taking over. I had to let out my monster, the one outside the codes. I thought of illuminations, the follies of the Middle Ages, ancient music, mystery, the Sphinx… I needed a non-human gaze, an observer. Out of all this, the cat appeared. Neither boy nor girl, neither good nor evil. I discover it as I embody it.

From the very first performance, I needed this costume. Even if I sang only once in my life, for that one time I had to have the costume, no matter the cost. It was vital, hiding to better show myself. Since then I have understood that this costume is a portal. It is not even really a cat anymore, in fact. It has become a chimera, a hybrid creature opening onto imagination. It allows me to embody strangeness, to explore another point of view, to push past the barrier of my own vision, to open up, to step aside in order to discover. Wider.

Temple Magazine

You also mentioned this invented language, this way of singing that frees you from literal meaning. How did it come about? Do you want to make it into a constructed language?

Lutèce Lockness

Not at all. It is not a language, well, it is the language of dreams. You should not look for words or sentences. In fact, I have been singing since I was a child. I learned by listening, by imitating. I have always sung in “yogurt,” in chat-rabia. Le Châ speaks this language. And it became a means of expression.

It allows me to focus on something else entirely, instead of fixing the story of my song with words. That does not mean that each song does not have its own subject or precise story! But it is present in another way, not through words. I have recently told myself that my real instrument is my voice, my voice in my body. That is how I make music, not through words. At least for now.

Temple Magazine

How do you actually work? Do you record yourself? How does a song come to life for you?

Lutèce Lockness

These are very intimate moments, often alone in my room, with very basic equipment. For the first song I had two microphones balancing inside my felt-tip box, I was at my desk and I closed my eyes. I played the bouzouki, I improvised, I searched for sequences of notes that touched me. When something resonated inside me, I recorded the sequence, I listened back, I searched for voices. I tried several voice options, several kinds of emotions, several scenarios in my head. Different characters. I experimented with the sounds of my voice, I discovered. I dug toward textures that creaked if it felt too obvious. At the same time I listened to a lot of music to soak myself in other things and to mix different worlds.

I also improvise a lot over music that is not mine, I jam with YouTube. It allows me to explore different scales, like training. And it comes back later, in my songs. I record myself constantly. Then I listen, sometimes I send the recordings to two or three close people who are good anchors for me. Or I keep them and rediscover them later, sometimes a year later. And then, with new eyes, with new musicality, I start something again from that. It is intuitive. It takes time and a song is made of multiple layers, temporal and emotional. It is not so separate from my life. It balances it. It is in tandem. I sing, I record, I go live, I come back, I listen, I cry, I sing again. Also I often compose while thinking of my next concert, I project myself into the space, it lights a fire inside me.

Temple Magazine

So on stage, a live performance can completely shift depending on your mood?

Lutèce Lockness

Well, yes and no. But that’s what I find crazy since I started performing, it’s only been a year. There’s such a gap between intimate creation and being on stage. They are two different jobs. Recording a song and playing it again is also a kind of time travel. But for me, each performance is a total unveiling. It’s very emotionally intense. Before and after, I’m shaken. A friend once told me it was “cat-seed”… because the cat plants seeds and sometimes it’s painful.

On stage, I don’t feel well and at the same time, it’s a feeling that touches the sublime, it’s extreme sport, a kind of parachute jump, but I always land on my feet. For now.

My goal is to express emotion, not to “sing well”—well, “singing well” is about being right, in the moment. What I sing is a direct translation of a feeling, but I am also an open score of the song’s story and its subject. Someone once told me I should “translate” what I sing, but I don’t want to. The translation is already there: it’s sonic, physical. It’s already a language in itself. Each song has its thread, its backdrop, its panel of vocal sounds and emotions, and on stage I have the space to weave with what is happening in the moment. So yes, there’s room for maneuver depending on the lived experience of the live performance, which allows each concert to adapt.

Temple Magazine

You also talk about journeys, exploration through listening. Are these journeys you’d like to make physically, or is it only through listening?

Lutèce Lockness

For now, I discover through listening. But I want to go discover high culture sounds. I’d like to go to Japan… in Asia, in Africa… in Mongolia! All these places I don’t know except through a screen or through music. I want to explore sonorities yes, instruments, traditional drums and see what it triggers, and play with that, cut and paste all that into new interwoven worlds. Not to integrate a style, but to feed the phonetic alphabet of Le Châ! The investigation is infinite.

Temple Magazine

You’re preparing an album, right? How are you approaching this step?

Lutèce Lockness

Yes, it’s the first time I’m doing this. And it’s yet another process, very different from composing alone in my room. What’s great is that I get along very well with the label team with whom we’re releasing the record “Le Châ.” Pan European allows me to have someone else besides me, invested in the release of the record. Without that, you feel very alone. It creates real support to move forward, to anchor, to accept the state of the sound, to have another ear.

Making a record feels like writing an epic.

At first, I wanted to re-record everything in the studio, “the proper way.” But Arthur from the label reminded me what Le Châ was. And finally, we decided to keep the raw recordings, born from my confidences in my room. The very first takes. The birth of the songs. At the moment when I was composing without thinking of an album, just letting things out in my intimate cocoon. And in fact, those versions, with wrong notes sometimes, a badly recorded bouzouki, carried such a true emotion that we wanted to keep them as a base. Afterwards, I rework them by adding layers. And in any case I had already built my live performances from these first drafts, later inviting other friends and artists to play on them, following very precise directions of Le Châ of course.

For the live shows, that’s already more or less how I do it: a very light first improvisation, just an intention or chords, and then I develop. I add sounds—frogs, spaceships, thunder— depending on the universe I project. I tell myself: “Where are we? Who am I singing for? For frogs? Okay, then we’re near a swamp.” I build a setting like a little film around each song. Sometimes it’s a Lynch film or a Miyazaki one. Other times, we’re under the full moon, in the mud, with creatures and insects. With fire. I also sing for the dead. And from there, I invite other musicians, I tell them about this world, the story of the song, even if it’s very open. I tell them, for example: “Here, I’d like to hear a kind of electricity in the air. Here’s a loop of the song where you could appear, if it speaks to you, play.” Or “Here are my notes and my emotion, listen to this.” And they answer me, I receive material, sometimes ten minutes of hurdy-gurdy drone, or an entire organ piece played by Jean Rondeau. Then I cut, and I recompose on top again. An exquisite corpse. It’s lacework, an assemblage of fragments and points of view.

Temple Magazine

And musical collaborations, that’s not a format you’ve experimented with live yet?

Lutèce Lockness

Not yet, but I’d like to. Now, while working on the tracks for the mix, I realize I want to move towards something more orchestral, wider, even freer live. For now I launch the backing track myself on stage and I play on top, but I dream of having jam moments live. With bases, of course. Because in my songs, there’s an orchestra accompanying me! One day they will all play around Le Châ on stage. That would be magnificent.

Inviting other musicians on stage would also shift the gaze a little, because I feel that for now, people are mostly looking at Le Châ. And that’s normal, the show is still short, it’s a real encounter with him. But Le Châ is just a door to imagination and music. It’s not the subject itself. It opens onto other worlds.

Temple Magazine

And for you, this character helped you move towards music.

Lutèce Lockness

Yes, it led me to music, but not only that. It also made me dream of images. I had never imagined making a film. I thought it was completely crazy, too complex. But with Le Châ, I want to propose visions, to explore image differently. It pushes me to work with visual artists, and to create together, the same way as with musicians. There are entire worlds to invent, to develop. And at the same time, there are already anchor points that Le Châ proposes. It allows ego to dissolve, to give rather than to take. It’s a call for collective creation — visual, musical, narrative. I feel like everything is still to be done, and that it’s infinite. It carries me.

Le Châ is not fixed. It’s a chimera, a password, a vehicle. I want to make it mutate: it can become a woman, or travel through time… It’s magical. It’s in permanent transformation. And that’s what I love.

Photos credits

@baptista.numero8

@igz_d8

@anjjacorh

@pierretopire

@pseudohugo

@margellea