l’idiot utile

October 2022

l’idiot utile is a journal that discusses clothes, fashion, its images, its aesthetics, its economy and its jobs.

Initiated in 2019 and entirely self-produced, l’idiot utile is a proposal by photographer Hubert Crabières, bookseller Alexis Etienne, graphic designer Hezin O and designer Josiane Martinho.

Temple Magazine

Can you tell us about the genesis of l’idiot utile?

Hubert Crabières

The title comes from a personal experience, but one that happens to be shared by many people I know in the creative community. I was working on a shoot for a magazine a few years ago, it was a special editorial for a brand, and I wasn't paid for the preparation nor for the shoot itself. The brand used these pictures for their website, on their social networks, etc., I thought I just produced free pictures for a brand that had a lot of money and it's not the first time, I'm really the useful idiot “l’idiot utile” of this system. So, it started from an experience that is, again, I think quite shared. But the idiot, if he is someone who doesn't know, can also be the one who wants to ask himself questions (and to ask them even more frontally because he is an idiot). The idea of creating this magazine was originally to set up an approach that would be useful to us, so that it could perhaps be useful to others in a second time. Moreover, for a magazine that is about fashion, we thought it was funny to have a lame and not at all catchy name, we were even afraid of the refusal of the contributors because of this name that sounds like an insult, finally it allows a clarity of the conditions of the invitation.

The space of the self-financed magazine allows us to experiment, to test ideas without the need of a prior approval from the milieu that gives you your chance or not or not completely. It's about giving ourselves our own opportunities with the least amount of compromise possible and it's about having a platform in which we can think very directly about the political issues involved in the very creation of a journal.

l’idiot utile is co-created with Alexis Etienne, who takes care of all the editorial direction. For the text part, he paid all the contributors of the articles (from writing to translation). For him, it is also a way to show that it is possible. There are so many publications and big magazines that ask for work and do not pay. It's an ideological choice.

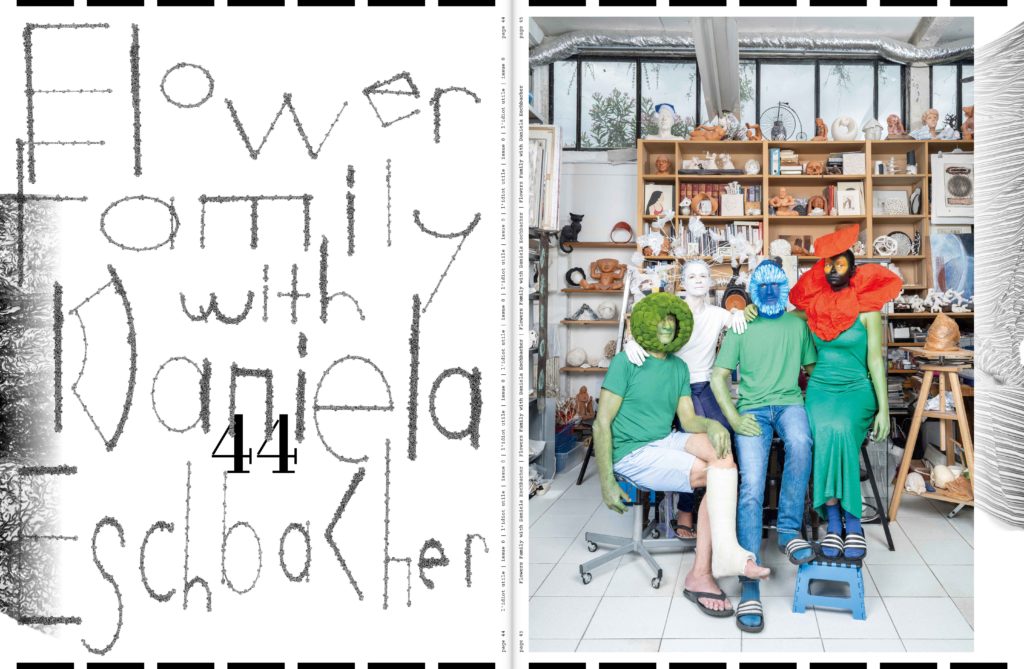

On my side I took care of the art direction and all the photographs and Josiane Martinho did the fashion direction. She thought and created clothes for the magazine, and at the same time she thought about the question of clothing in a more general way, by inviting other designers. Each of us also interviewed people who we thought could bring some solutions or at least perspectives to our problems. Hezin O, the graphic designer, had carte blanche for the graphic design of the useful idiot. The idea is that everyone can find himself in the result of the work invested.

Temple Magazine

Yes, we feel that it's a co-creation.

Hubert Crabières

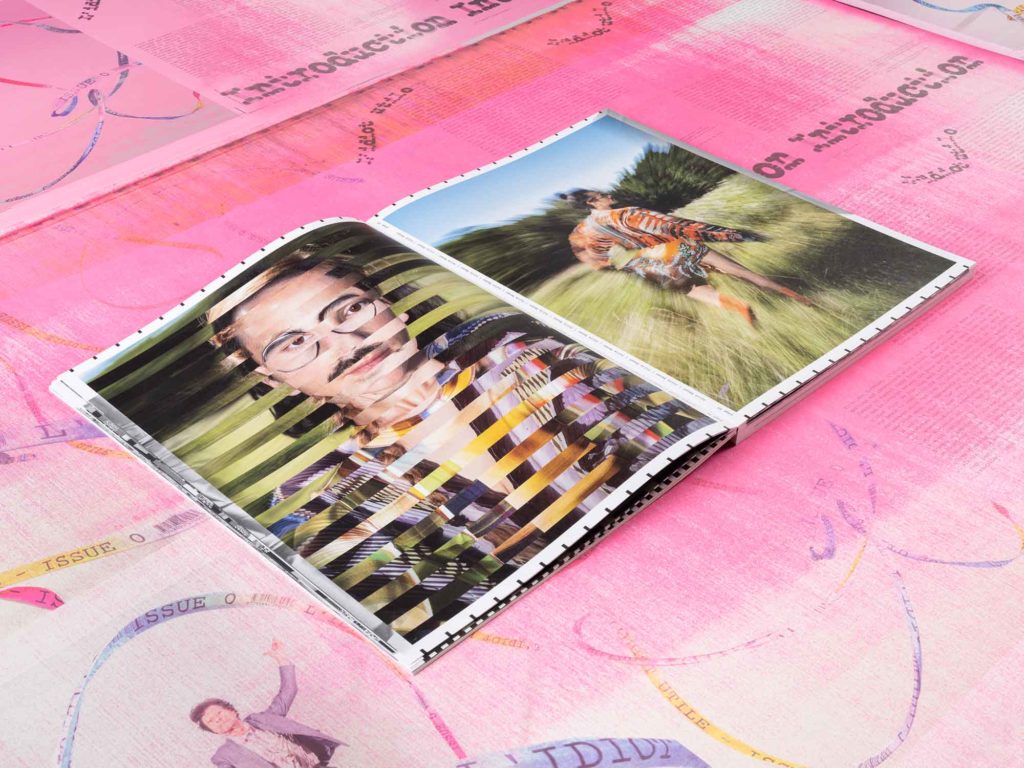

It's as much my work as Alexis's, Hezin's or Josiane's... Over the years, I haven't developed a hyper-fetishistic relationship with my images. When you accept to share your images on social networks, you also accept the idea that these things circulate, that they don't belong to you anymore. For the magazine, Hezin has for example total freedom to experiment with and appropriate them like all the materials that are shared with him.

Temple Magazine

There are 17 series of images in this first issue, what guided their creation?

Hubert Crabières

I have lists of ideas and projects that I want to do, and I am waiting for the opportunity to do them. There is no theme or general direction for l’idiot utile because we felt that was the best way to move forward. The direction was made by our identities and their expressions and according to the demands of the time too. l’idiot utile had to come out at some point, so we had to put a stop to it. Each of the series required encounters, questioning the game with the printed image, which is already of great interest to me in my work in general.

Temple Magazine

In the interviews, there is a real desire to show what fashion is today, the relationship to this industry as a young designer, how to be paid and treated properly. Will your next issue be in this vein, defending this same theme?

Hubert Crabières

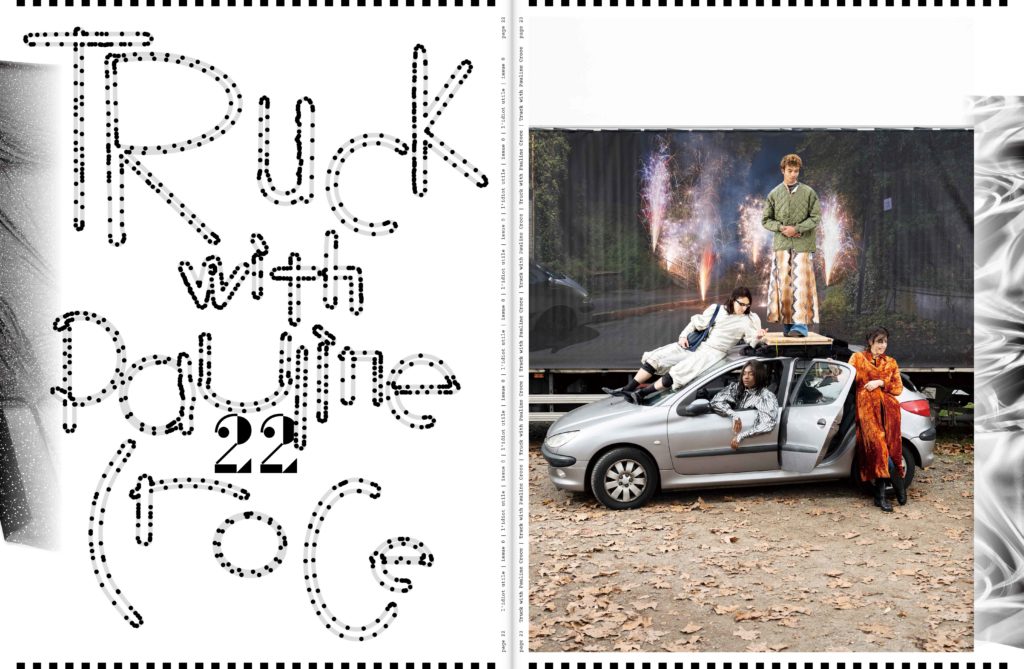

Yes, and the urgent aspect that we wanted to address with Alexis Etienne is the economic question. In the capitalist system, when something is not opposed to growth, or can even contribute to it, the system appropriates it directly. Like the current false good conscience that brands are desperate to have by playing the inclusiveness card. All social struggles have now been aestheticized. It seems to us that the inequalities of salaries in relation to the distribution of work, in the fashion industry, which is doing so well, raise the right questions. We have been looking for actors who want to emancipate themselves from this, and without doubt the result can never be completely convincing. It can at least be inspiring. In particular, we have an interview with Pauline Croce who was a fashion stylist and became a costume designer for the cinema, a milieu with another history and other problems but which suits her better. The cinema is a better unionized, better protected environment, which for example has managed to preserve the intermittent model. But the interview with Pauline Croce shows that other problems exist, especially on small productions where she feels much better than on fashion shoots.

These notions are deeply contradictory to the totally immaterial and depoliticized "dream" perpetuated by the discourses produced on the creative professions, and the fashion market is undoubtedly one of the most efficient to spread them.

The visual arts and fashion worlds have undeniably competitive aspects. Pauline Croce's comments on her experience in the film industry and Adeline André's work in collaboration with the theater and opera are inspiring in order to get out of the ethereal representations of the creator whose ideas are so beautiful that they will eventually be born in the daytime.

Established systems necessarily resist these demands for change, for dialogue between the different professions. The individual enhancement, the competition of scholarships and prizes provoke the necessary agitation to elude the need to study these other economic solutions. Our magazine wishes to put forward other faces or more known faces but to show that the reality of their work and the way they have to deal with it produces original and reflective forms.

Temple Magazine

And also, to emancipate oneself from the editorial which becomes a brand campaign.

Hubert Crabières

We wondered how to do fashion without doing communication and put ourselves at the service of a brand. Some of the designers' pieces are two or three years old, given the time it took to bring out the magazine. So, by that time frame, it just can't be a 2022-2023 campaign. We were more interested in the whole process, to also break the absurd temporality of fashion seasons. Even independent brands have to follow a high demand of production, fashion shows per season, showrooms, campaigns, etc., when they don't even have the financial resources and certainly not those of the big groups that dictated the rules. They can't keep up with the competition and yet social networks encourage them to invest more and more in order to appear to be at the level of producing impactful images. However, the game becomes impossible to keep, the rules must be changed, and they must emancipate themselves from this success. It may then be a question of choosing to value something else. As long as we all aspire to a success defined by an oppressive and destructive system, we will not get out of it.

Temple Magazine

Can you tell us about the genesis of l’idiot utile?

Hubert Crabières

The title comes from a personal experience, but one that happens to be shared by many people I know in the creative community. I was working on a shoot for a magazine a few years ago, it was a special editorial for a brand, and I wasn't paid for the preparation nor for the shoot itself. The brand used these pictures for their website, on their social networks, etc., I thought I just produced free pictures for a brand that had a lot of money and it's not the first time, I'm really the useful idiot “l’idiot utile” of this system. So, it started from an experience that is, again, I think quite shared. But the idiot, if he is someone who doesn't know, can also be the one who wants to ask himself questions (and to ask them even more frontally because he is an idiot). The idea of creating this magazine was originally to set up an approach that would be useful to us, so that it could perhaps be useful to others in a second time. Moreover, for a magazine that is about fashion, we thought it was funny to have a lame and not at all catchy name, we were even afraid of the refusal of the contributors because of this name that sounds like an insult, finally it allows a clarity of the conditions of the invitation.

The space of the self-financed magazine allows us to experiment, to test ideas without the need of a prior approval from the milieu that gives you your chance or not or not completely. It's about giving ourselves our own opportunities with the least amount of compromise possible and it's about having a platform in which we can think very directly about the political issues involved in the very creation of a journal.

l’idiot utile is co-created with Alexis Etienne, who takes care of all the editorial direction. For the text part, he paid all the contributors of the articles (from writing to translation). For him, it is also a way to show that it is possible. There are so many publications and big magazines that ask for work and do not pay. It's an ideological choice.

On my side I took care of the art direction and all the photographs and Josiane Martinho did the fashion direction. She thought and created clothes for the magazine, and at the same time she thought about the question of clothing in a more general way, by inviting other designers. Each of us also interviewed people who we thought could bring some solutions or at least perspectives to our problems. Hezin O, the graphic designer, had carte blanche for the graphic design of the useful idiot. The idea is that everyone can find himself in the result of the work invested.

Temple Magazine

Yes, we feel that it's a co-creation.

Hubert Crabières

It's as much my work as Alexis's, Hezin's or Josiane's... Over the years, I haven't developed a hyper-fetishistic relationship with my images. When you accept to share your images on social networks, you also accept the idea that these things circulate, that they don't belong to you anymore. For the magazine, Hezin has for example total freedom to experiment with and appropriate them like all the materials that are shared with him.

Temple Magazine

There are 17 series of images in this first issue, what guided their creation?

Hubert Crabières

I have lists of ideas and projects that I want to do, and I am waiting for the opportunity to do them. There is no theme or general direction for l’idiot utile because we felt that was the best way to move forward. The direction was made by our identities and their expressions and according to the demands of the time too. l’idiot utile had to come out at some point, so we had to put a stop to it. Each of the series required encounters, questioning the game with the printed image, which is already of great interest to me in my work in general.

Temple Magazine

In the interviews, there is a real desire to show what fashion is today, the relationship to this industry as a young designer, how to be paid and treated properly. Will your next issue be in this vein, defending this same theme?

Hubert Crabières

Yes, and the urgent aspect that we wanted to address with Alexis Etienne is the economic question. In the capitalist system, when something is not opposed to growth, or can even contribute to it, the system appropriates it directly. Like the current false good conscience that brands are desperate to have by playing the inclusiveness card. All social struggles have now been aestheticized. It seems to us that the inequalities of salaries in relation to the distribution of work, in the fashion industry, which is doing so well, raise the right questions. We have been looking for actors who want to emancipate themselves from this, and without doubt the result can never be completely convincing. It can at least be inspiring. In particular, we have an interview with Pauline Croce who was a fashion stylist and became a costume designer for the cinema, a milieu with another history and other problems but which suits her better. The cinema is a better unionized, better protected environment, which for example has managed to preserve the intermittent model. But the interview with Pauline Croce shows that other problems exist, especially on small productions where she feels much better than on fashion shoots.

These notions are deeply contradictory to the totally immaterial and depoliticized "dream" perpetuated by the discourses produced on the creative professions, and the fashion market is undoubtedly one of the most efficient to spread them.

The visual arts and fashion worlds have undeniably competitive aspects. Pauline Croce's comments on her experience in the film industry and Adeline André's work in collaboration with the theater and opera are inspiring in order to get out of the ethereal representations of the creator whose ideas are so beautiful that they will eventually be born in the daytime.

Established systems necessarily resist these demands for change, for dialogue between the different professions. The individual enhancement, the competition of scholarships and prizes provoke the necessary agitation to elude the need to study these other economic solutions. Our magazine wishes to put forward other faces or more known faces but to show that the reality of their work and the way they have to deal with it produces original and reflective forms.

Temple Magazine

And also, to emancipate oneself from the editorial which becomes a brand campaign.

Hubert Crabières

We wondered how to do fashion without doing communication and put ourselves at the service of a brand. Some of the designers' pieces are two or three years old, given the time it took to bring out the magazine. So, by that time frame, it just can't be a 2022-2023 campaign. We were more interested in the whole process, to also break the absurd temporality of fashion seasons. Even independent brands have to follow a high demand of production, fashion shows per season, showrooms, campaigns, etc., when they don't even have the financial resources and certainly not those of the big groups that dictated the rules. They can't keep up with the competition and yet social networks encourage them to invest more and more in order to appear to be at the level of producing impactful images. However, the game becomes impossible to keep, the rules must be changed, and they must emancipate themselves from this success. It may then be a question of choosing to value something else. As long as we all aspire to a success defined by an oppressive and destructive system, we will not get out of it.