Meriem Bennani

November 2025

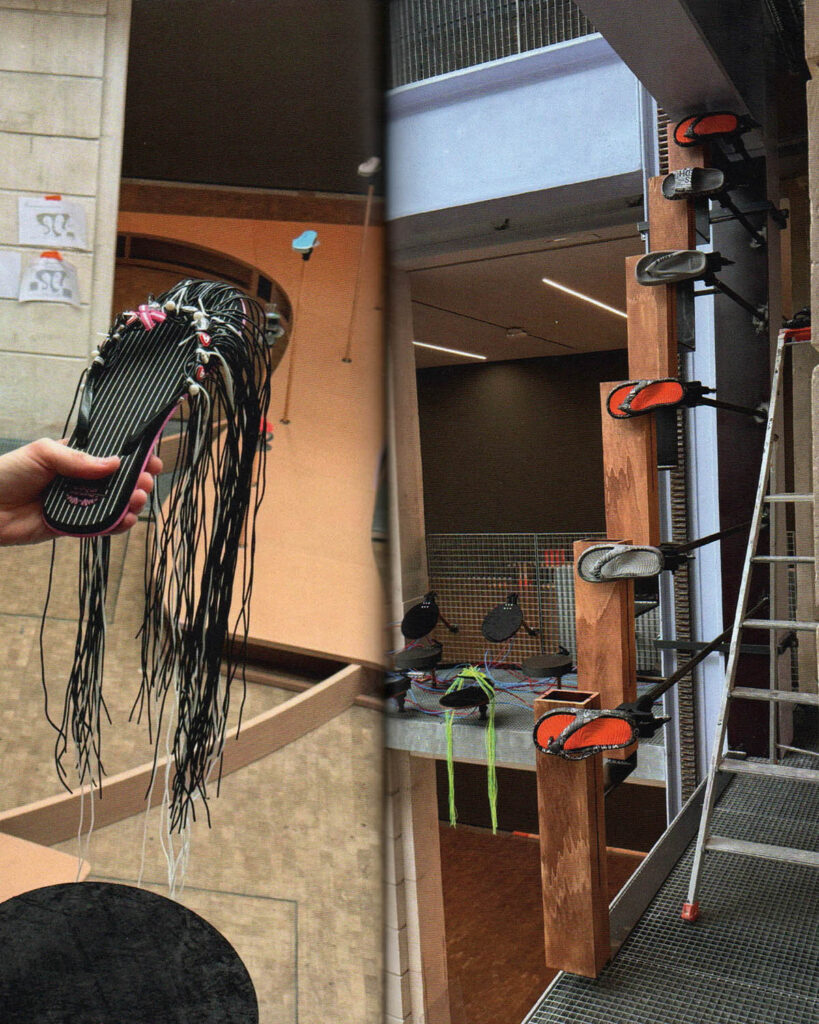

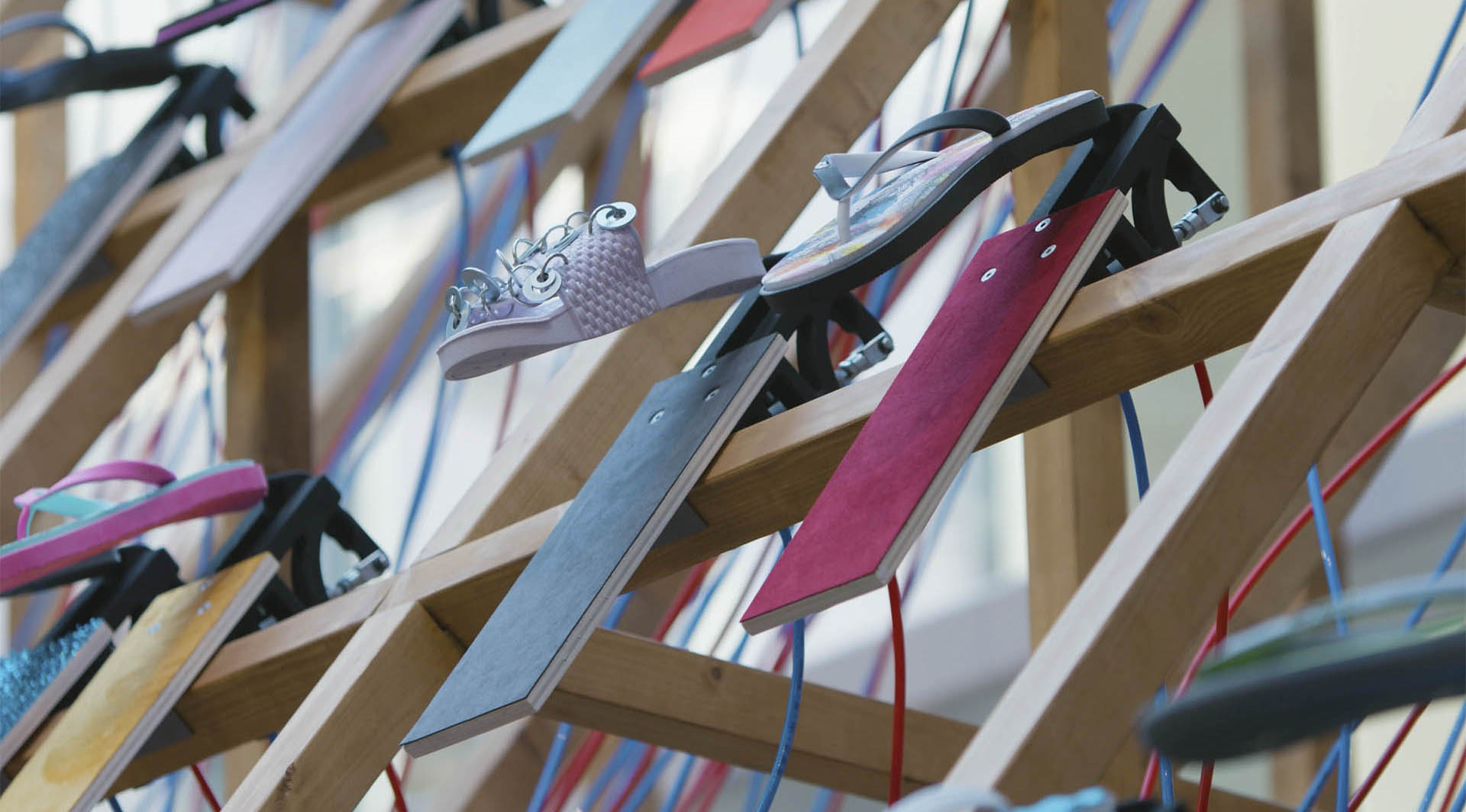

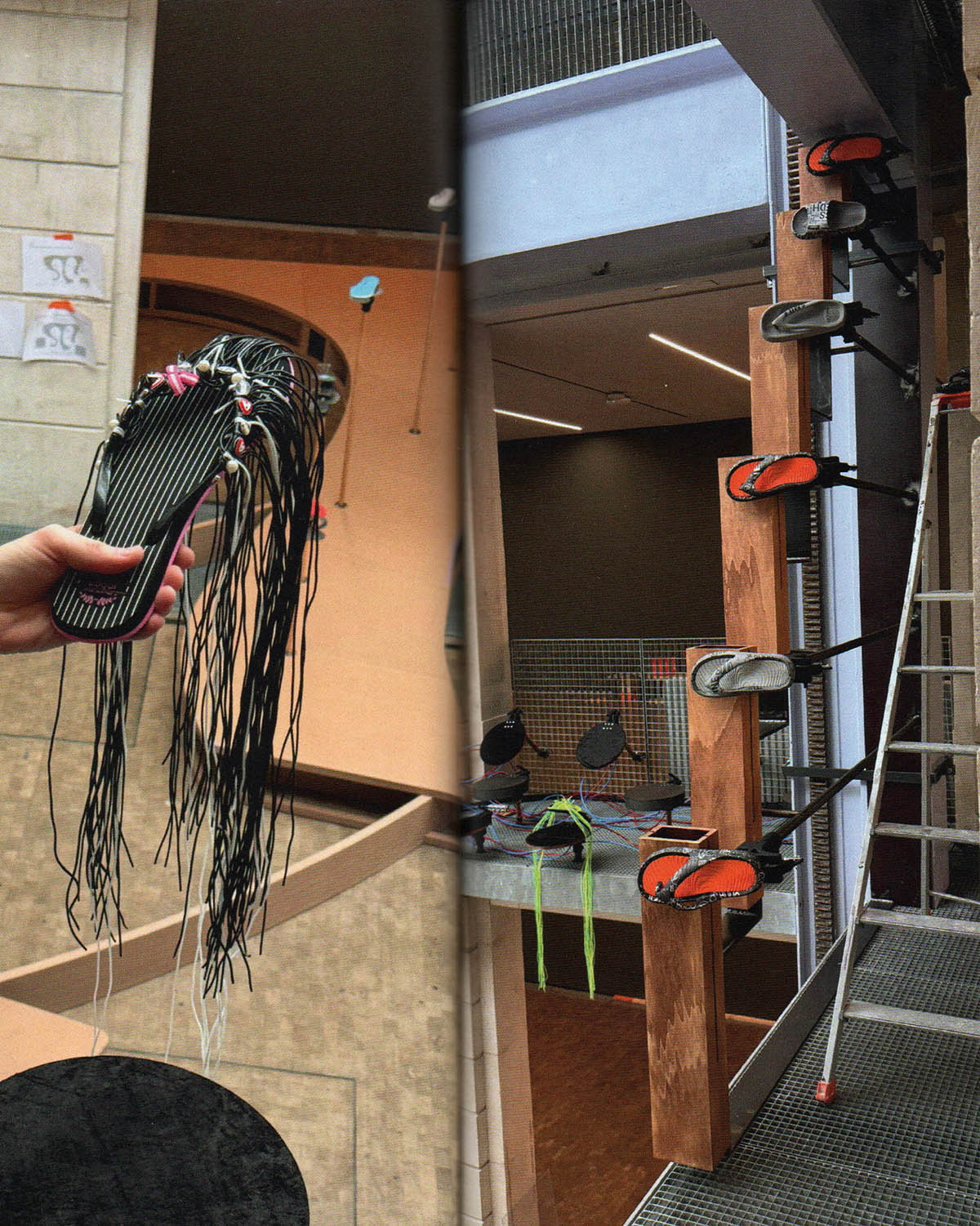

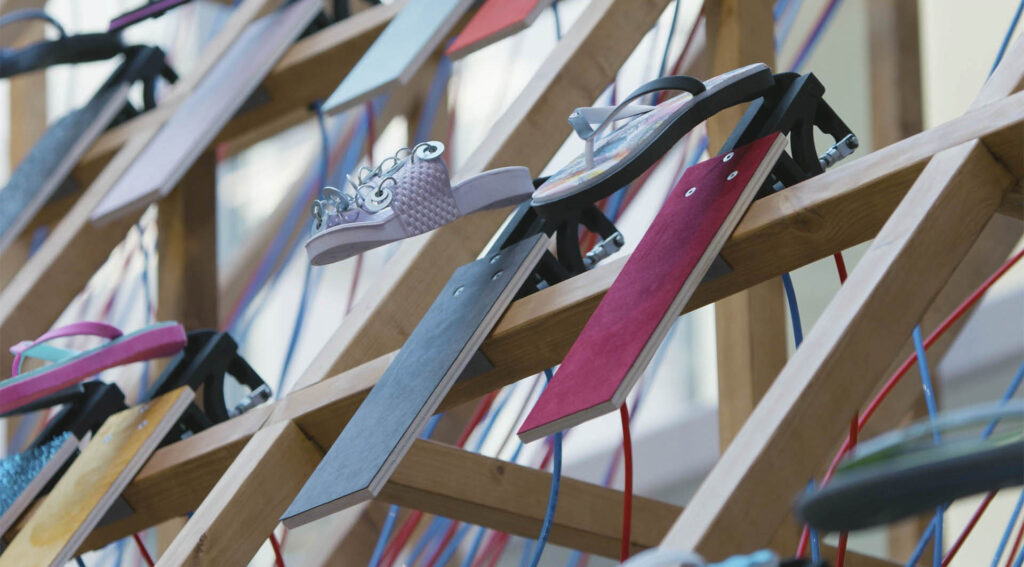

For her solo exhibition at Lafayette Anticipations, Moroccan-born, New York–based artist Meriem Bennani presents a monumental sound installation that turns the foundation into a vast acoustic instrument. Spanning the full height of the building, Sole crushing gathers nearly 200 flip-flops and sandals mounted on a pneumatic system and arranged with precision. These shoes strike different surfaces, producing percussive sounds that evoke crowds, protests, stadium chants or the Moroccan dakka marrakchia.

Originally shown in the exhibition For My Best Family at Fondazione Prada (2024–25), the piece has been re-imagined for Lafayette Anticipations with a new musical score by Reda Senhaji (aka Cheb Runner) and a layout adapted to the gallery’s vertical architecture.

©Meriem Bennani, Lafayette Anticipations

Temple Magazine

At Fondazione Prada, For My Best Family brought together For Aicha and an earlier version of Sole crushing. At Lafayette Anticipations, the installation now stands alone and occupies the entire building. What does that change in the way it tells its story, and how did you adapt it to this very vertical space?

Meriem Bennani

For Aicha, made with Orian Barki, and Sole crushing are two completely different works. At Fondazione Prada they were shown together because it was a large exhibition I had worked on for two or three years, with two major pieces that shared themes, but they aren’t directly connected.

At Lafayette Anticipations, I focused on a new version of Sole crushing without thinking about For Aicha. The space is notoriously complicated – everyone says so – but it’s also modular, which is valuable. It’s very different from the Fondazione Prada space, even though it was designed by the same architect.

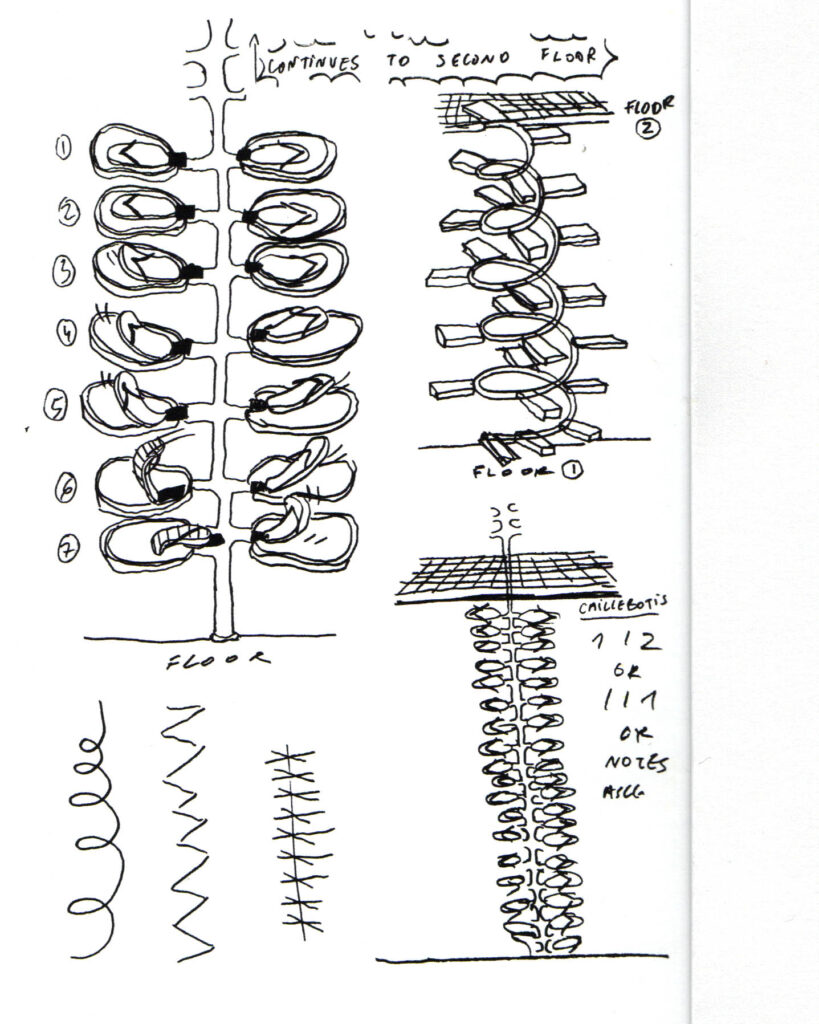

I enjoy the challenge of site-specific work. You let the architecture push you toward ideas you wouldn’t have had otherwise. A vertical version of Sole Crushing is something I never imagined. In the end it creates a kind of crushing effect when you arrive on the ground floor, and as you move through the building, the sound shifts depending on where you stand.

Temple Magazine

You composed the music with Reda Senhaji (aka Cheb Runner). How did the collaboration take shape? At what point does he enter your process? Do you imagine the mechanical systems first and he composes from there?

Meriem Bennani

Reda comes in fairly early because he has a strong understanding of instruments, how a material or a shape produces a sound and also a real command of electronic composition.

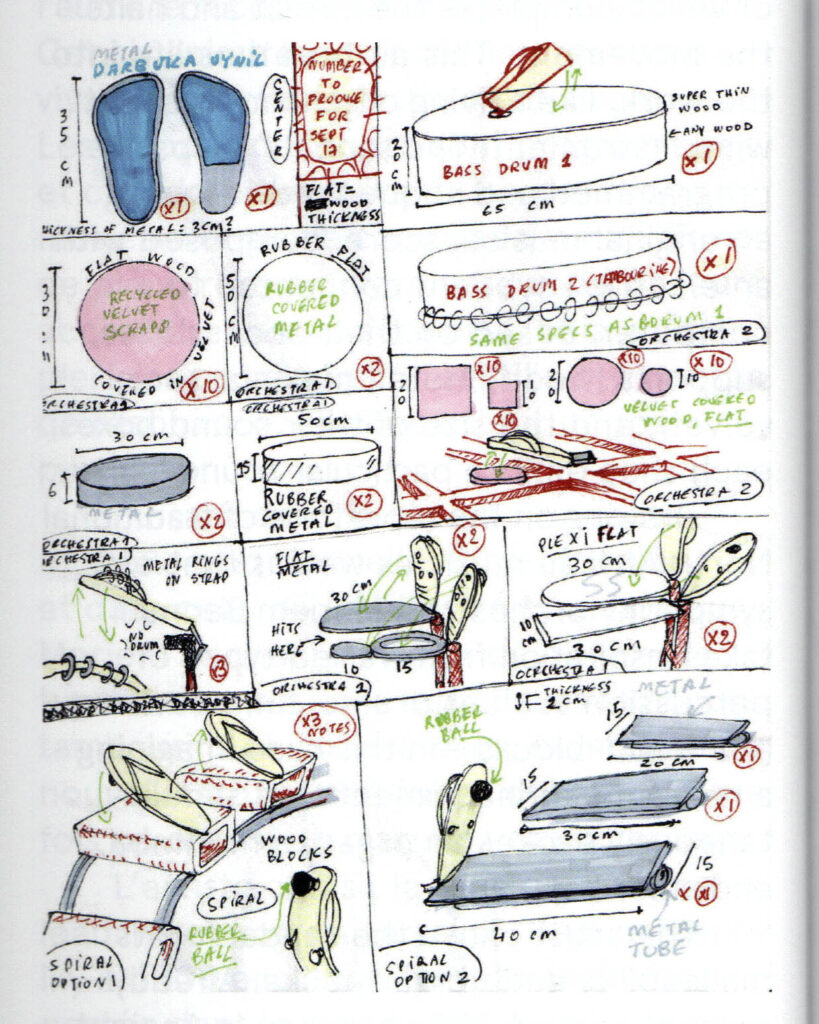

When we finalise the timbre of the instruments, the length of the tubes, the materials, which flip-flops to use, we do that together. The core of the installation is already there, but it’s with him that we really choose the sounds.

Many of the instruments already existed at Fondazione Prada. We had done sessions with a fabricator, cutting wood, testing materials, so Reda knew them well. At Lafayette Anticipations we added a few, but he already understood how they would sound.

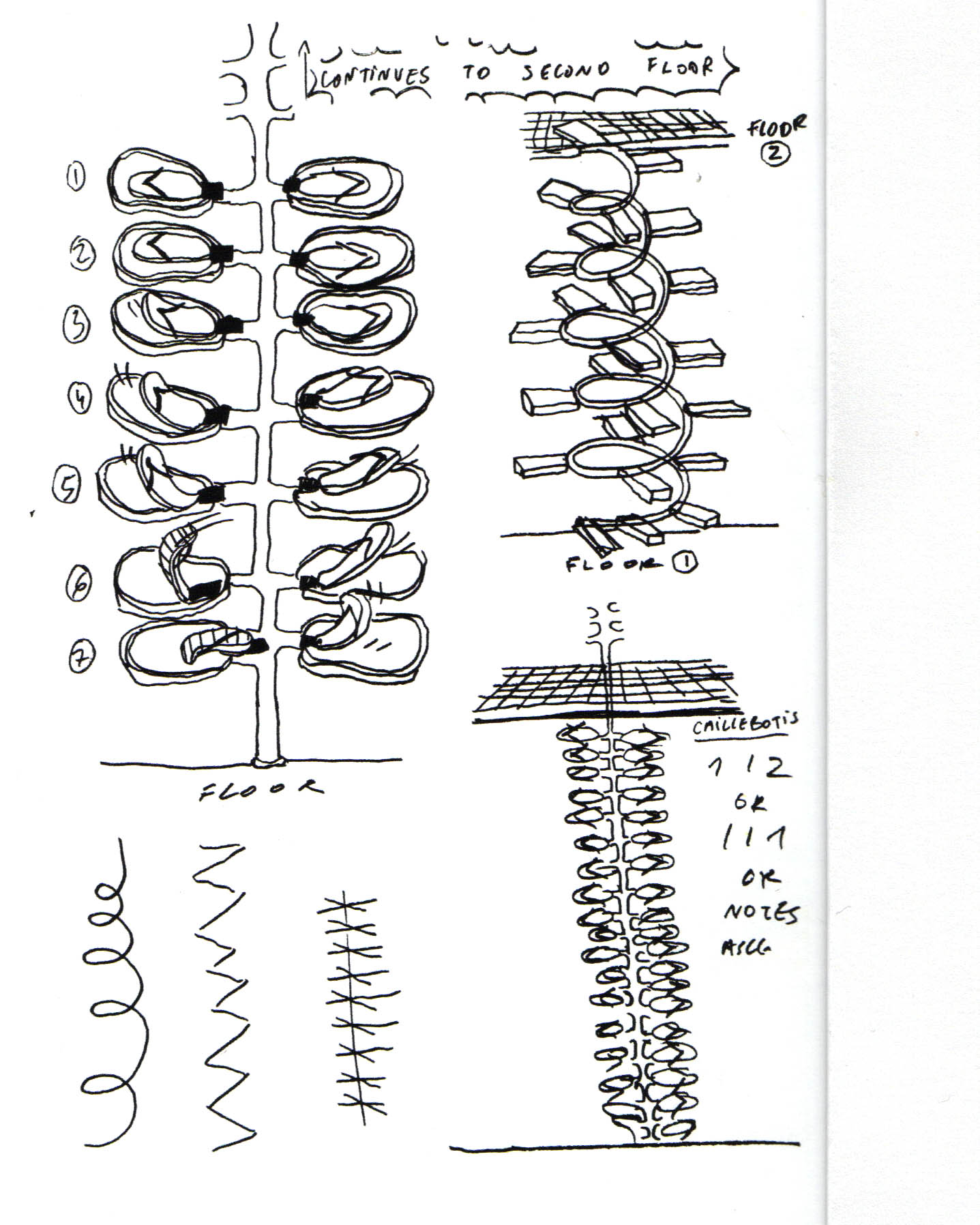

Once everything is installed, we compose inside the space. We had clear intentions linked to Moroccan rhythms. Then, depending on the architecture, we imagine effects: a “tornado” of notes activated from top to bottom, spatial movements, sequences. Reda improvises a lot. When a motif works, we record it, then assemble all the segments to create the final score.

Temple Magazine

And the choice of materials or the customisation of the flip-flops, is that guided by sound?

Meriem Bennani

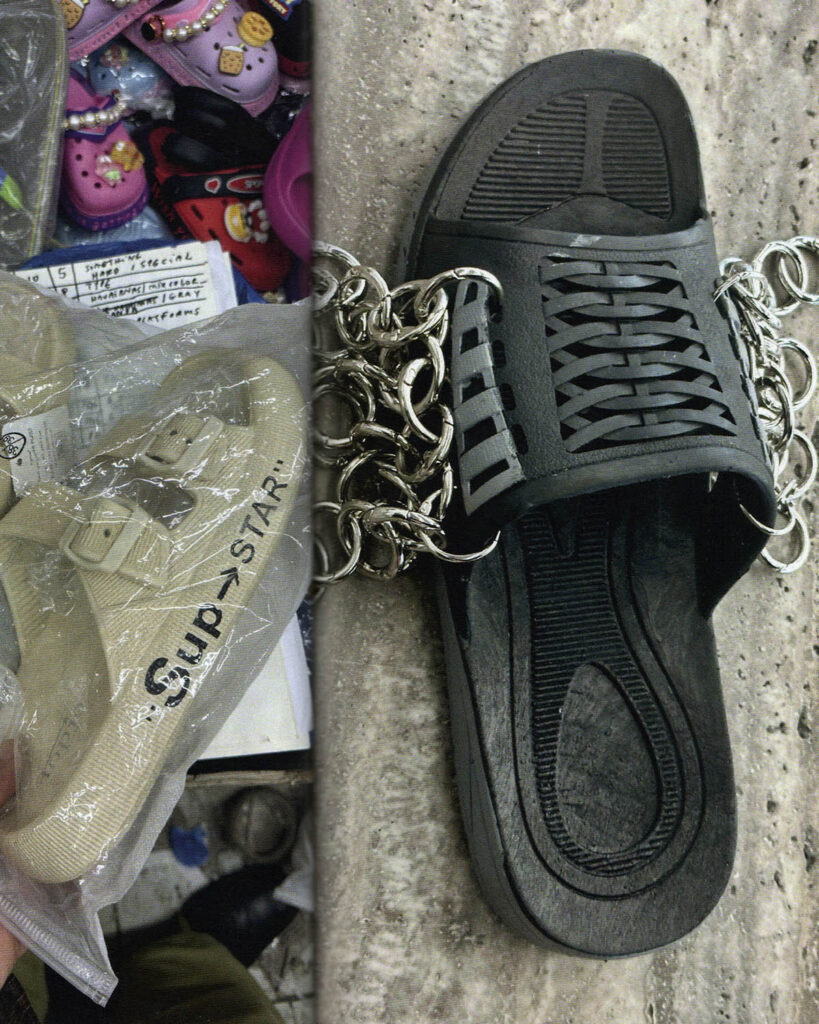

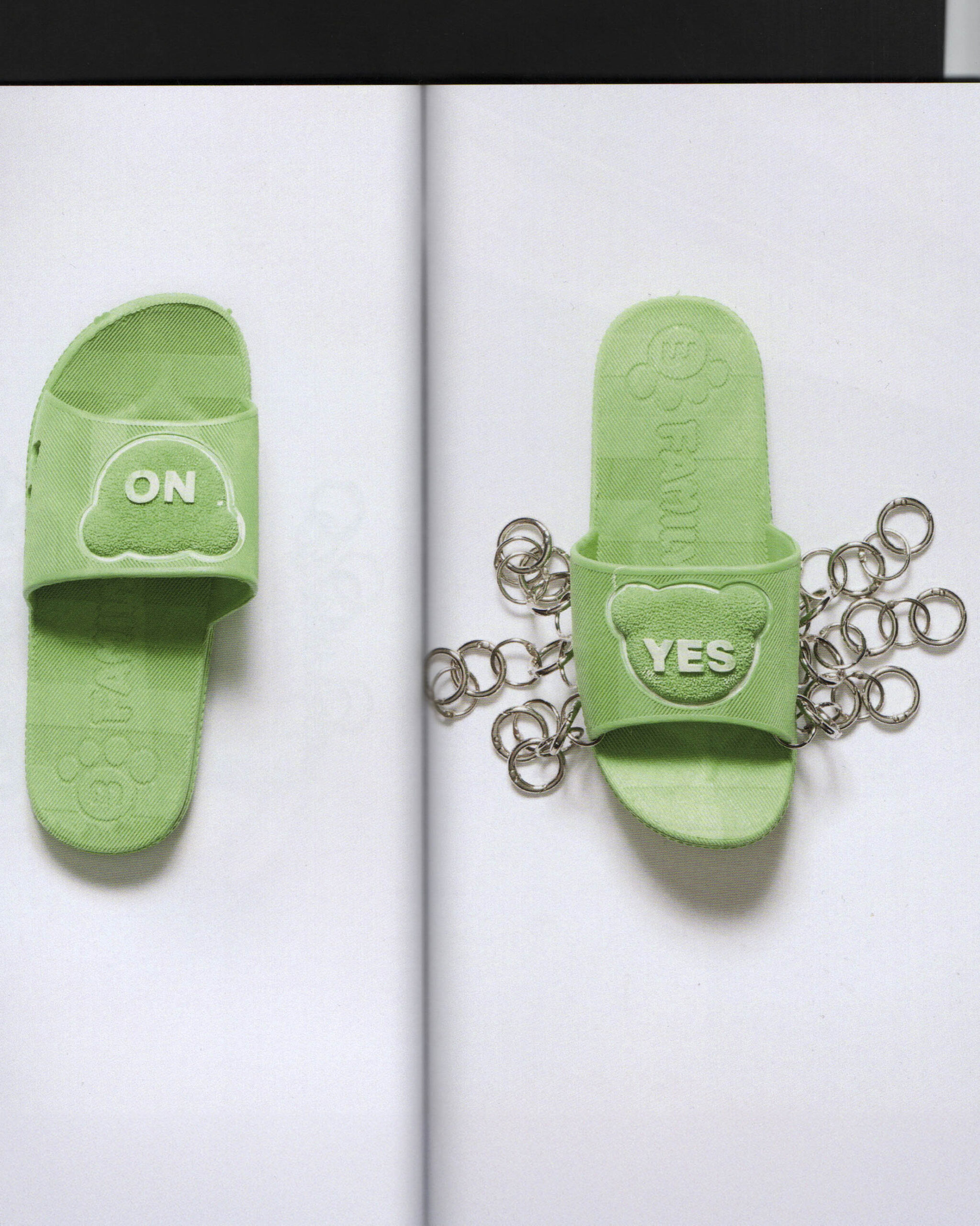

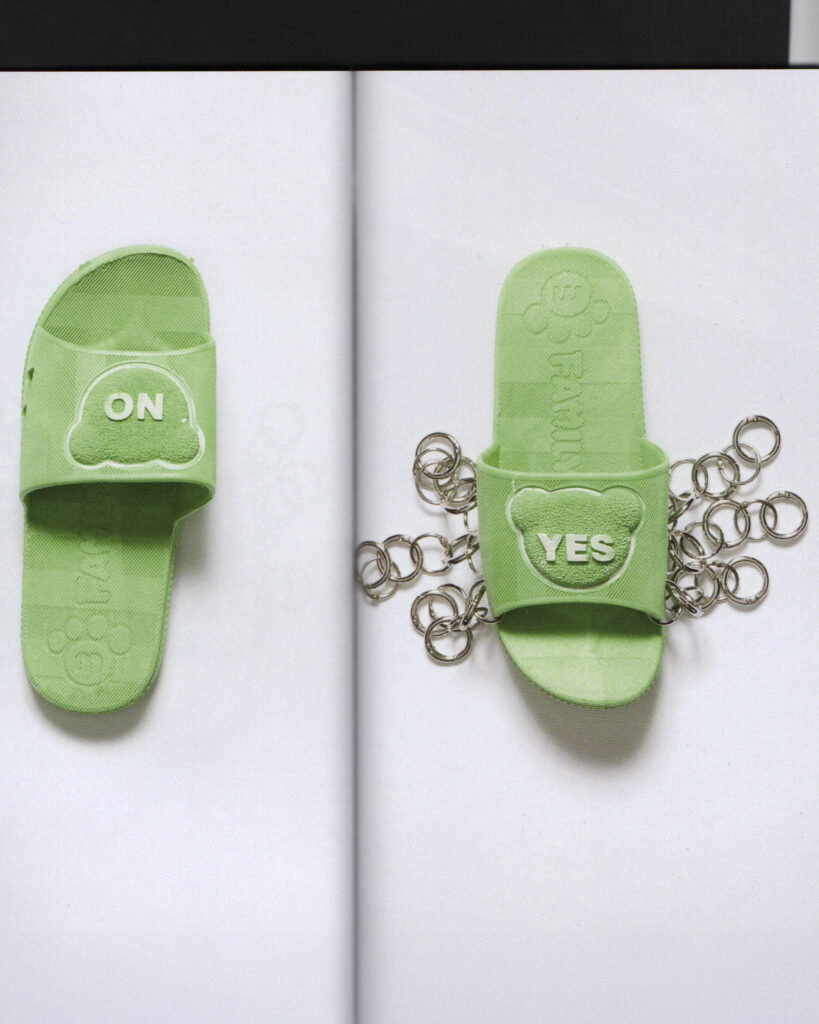

Yes. The soles produce different tones. Sometimes we add rings to create a shaker effect. Reda and I had shared videos of people making music with flip-flops and bamboo. A flip-flop is such a simple object that it gets reused for many things. We wanted an additional instrument that would give us more melodic notes, not only percussive ones.

Temple Magazine

Your work relies on very precise engineering. How do you actually build all of this? Do you have a technical background?

Meriem Bennani

No and that helps me. I can imagine things someone very technical might rule out immediately because they already know the limits.

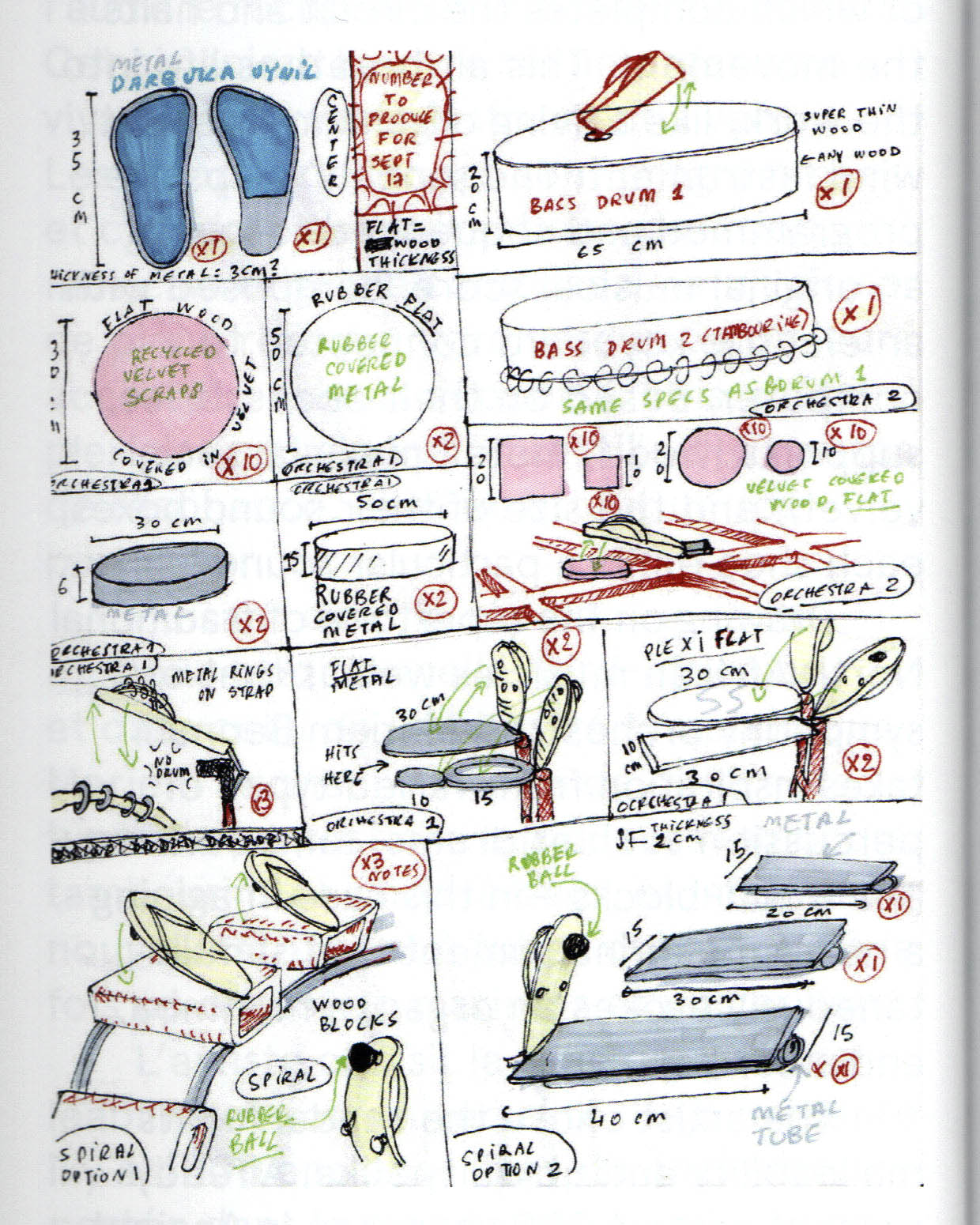

I start with hand drawings, then move everything into 3D. I recreate the exhibition space and draw the sculptures inside it. Then I work with fabricators whose job is to get as close as possible to the 3D drawings. They tell me clearly: this won’t hold, gravity won’t allow that. And I enjoy reinventing the sculptures based on those constraints. It pushes me toward unexpected forms.

For Sole crushing, Fondazione Prada suggested several possible systems, mechanical or electronic. I chose the pneumatic. I liked the idea of a system that works with air, that breathes – an organism with tubes. We chose to keep the tubes visible, in blue and red, like a blood system.

Temple Magazine

Drawing is very present in your work. What is its place today?

Meriem Bennani

It’s my first medium. For a long time I thought that was all I would do. Today I mostly draw sculptures, installations, film ideas or storyboards. I still make autonomous drawings when I can, but my studio has become an office full of computers rather than a drawing studio. When I have the chance to be in a real studio for a few days and make large drawings, I love it.

Temple Magazine

And movement? In your films, installations and sculptures, nothing is ever static.

Meriem Bennani

I’m very influenced by animation. I’ve been doing it for a long time, and I grew up with American cartoons. That shapes how I think about rhythm. Moroccan popular music too: the BPM is very fast. It influences my work a lot.

Temple Magazine

In works like 2 Lizards, Bouchra or Sole crushing, you move from animal avatars to personified objects. How do you choose these forms? What do these transformations allow you to express?

Meriem Bennani

It’s often intuitive. The lizards happened by chance. I had 3D characters, and Orian Barki chose two of them, and we started from there. For the flip-flop, it was its cartoon, like personality that attracted me. There isn’t always symbolic value behind it. I like these narrative prostheses, like sidekicks in Disney films. They lighten certain scenes, shift the tension. And in my early videos I used animated characters to manipulate reality, create links, remind the viewer that I’m present, that it’s a subjective version.

Temple Magazine

Sole crushing is immersive, almost entertaining, with a performative dimension. Does the word entertainment bother you? Or does it allow you to address political and cultural subjects differently?

Meriem Bennani

Not at all. You just have to understand what entertainment means. Distraction or entertainment are not anti-intellectual. It’s simply another approach.

My language borrows from music, cinema, television, reality TV. I have no limits. What interests me is why these forms are so popular and effective. I can borrow their codes and then turn them toward something else.

Temple Magazine

And finally: Sole crushing moves between celebration, orchestra and uprising. For you, what is it above all?

Meriem Bennani

I like to try and sustain a certain level of nuance and ambiguity.

Temple Magazine

At Fondazione Prada, For My Best Family brought together For Aicha and an earlier version of Sole crushing. At Lafayette Anticipations, the installation now stands alone and occupies the entire building. What does that change in the way it tells its story, and how did you adapt it to this very vertical space?

Meriem Bennani

For Aicha, made with Orian Barki, and Sole crushing are two completely different works. At Fondazione Prada they were shown together because it was a large exhibition I had worked on for two or three years, with two major pieces that shared themes, but they aren’t directly connected.

At Lafayette Anticipations, I focused on a new version of Sole crushing without thinking about For Aicha. The space is notoriously complicated – everyone says so – but it’s also modular, which is valuable. It’s very different from the Fondazione Prada space, even though it was designed by the same architect.

I enjoy the challenge of site-specific work. You let the architecture push you toward ideas you wouldn’t have had otherwise. A vertical version of Sole Crushing is something I never imagined. In the end it creates a kind of crushing effect when you arrive on the ground floor, and as you move through the building, the sound shifts depending on where you stand.

Temple Magazine

You composed the music with Reda Senhaji (aka Cheb Runner). How did the collaboration take shape? At what point does he enter your process? Do you imagine the mechanical systems first and he composes from there?

Meriem Bennani

Reda comes in fairly early because he has a strong understanding of instruments, how a material or a shape produces a sound and also a real command of electronic composition.

When we finalise the timbre of the instruments, the length of the tubes, the materials, which flip-flops to use, we do that together. The core of the installation is already there, but it’s with him that we really choose the sounds.

Many of the instruments already existed at Fondazione Prada. We had done sessions with a fabricator, cutting wood, testing materials, so Reda knew them well. At Lafayette Anticipations we added a few, but he already understood how they would sound.

Once everything is installed, we compose inside the space. We had clear intentions linked to Moroccan rhythms. Then, depending on the architecture, we imagine effects: a “tornado” of notes activated from top to bottom, spatial movements, sequences. Reda improvises a lot. When a motif works, we record it, then assemble all the segments to create the final score.

Temple Magazine

And the choice of materials or the customisation of the flip-flops, is that guided by sound?

Meriem Bennani

Yes. The soles produce different tones. Sometimes we add rings to create a shaker effect. Reda and I had shared videos of people making music with flip-flops and bamboo. A flip-flop is such a simple object that it gets reused for many things. We wanted an additional instrument that would give us more melodic notes, not only percussive ones.

Temple Magazine

Your work relies on very precise engineering. How do you actually build all of this? Do you have a technical background?

Meriem Bennani

Not at all, and that helps me. I can imagine things someone very technical might rule out immediately because they already know the limits.

I start with hand drawings, then move everything into 3D. I recreate the exhibition space and draw the sculptures inside it. Then I work with fabricators whose job is to get as close as possible to the 3D drawings. They tell me clearly: this won’t hold, gravity won’t allow that. And I enjoy reinventing the sculptures based on those constraints. It pushes me toward unexpected forms.

For Sole crushing, Fondazione Prada suggested several possible systems, mechanical or electronic. I chose the pneumatic. I liked the idea of a system that works with air, that breathes – an organism with tubes. We chose to keep the tubes visible, in blue and red, like a blood system.

Temple Magazine

Drawing is very present in your work. What is its place today?

Meriem Bennani

It’s my first medium. For a long time I thought that was all I would do. Today I mostly draw sculptures, installations, film ideas or storyboards. I still make autonomous drawings when I can, but my studio has become an office full of computers rather than a drawing studio. When I have the chance to be in a real studio for a few days and make large drawings, I love it.

Temple Magazine

And movement? In your films, installations and sculptures, nothing is ever static.

Meriem Bennani

I’m very influenced by animation. I’ve been doing it for a long time, and I grew up with American cartoons. That shapes how I think about rhythm. Moroccan popular music too: the BPM is very fast. It influences my work a lot.

Temple Magazine

In works like 2 Lizards, Bouchra or Sole crushing, you move from animal avatars to personified objects. How do you choose these forms? What do these transformations allow you to express?

Meriem Bennani

It’s often intuitive. The lizards happened by chance. I had 3D characters, and Orian Barki chose two of them, and we started from there. For the flip-flop, it was its cartoon, like personality that attracted me. There isn’t always symbolic value behind it. I like these narrative prostheses, like sidekicks in Disney films. They lighten certain scenes, shift the tension. And in my early videos I used animated characters to manipulate reality, create links, remind the viewer that I’m present, that it’s a subjective version.

Temple Magazine

Sole crushing is immersive, almost entertaining, with a performative dimension. Does the word entertainment bother you? Or does it allow you to address political and cultural subjects differently?

Meriem Bennani

Not at all. You just have to understand what entertainment means. Distraction or entertainment are not anti-intellectual. It’s simply another approach.

My language borrows from music, cinema, television, reality TV. I have no limits. What interests me is why these forms are so popular and effective. I can borrow their codes and then turn them toward something else.

Temple Magazine

And finally: Sole crushing moves between celebration, orchestra and uprising. For you, what is it above all?

Meriem Bennani

I like to try and sustain a certain level of nuance and ambiguity.