Oleg de La Morinerie

December 2025

for Temple Magazine issue 13, images by Margaux Salarino.

Agreste & associates at Oleg de La Morinerie.

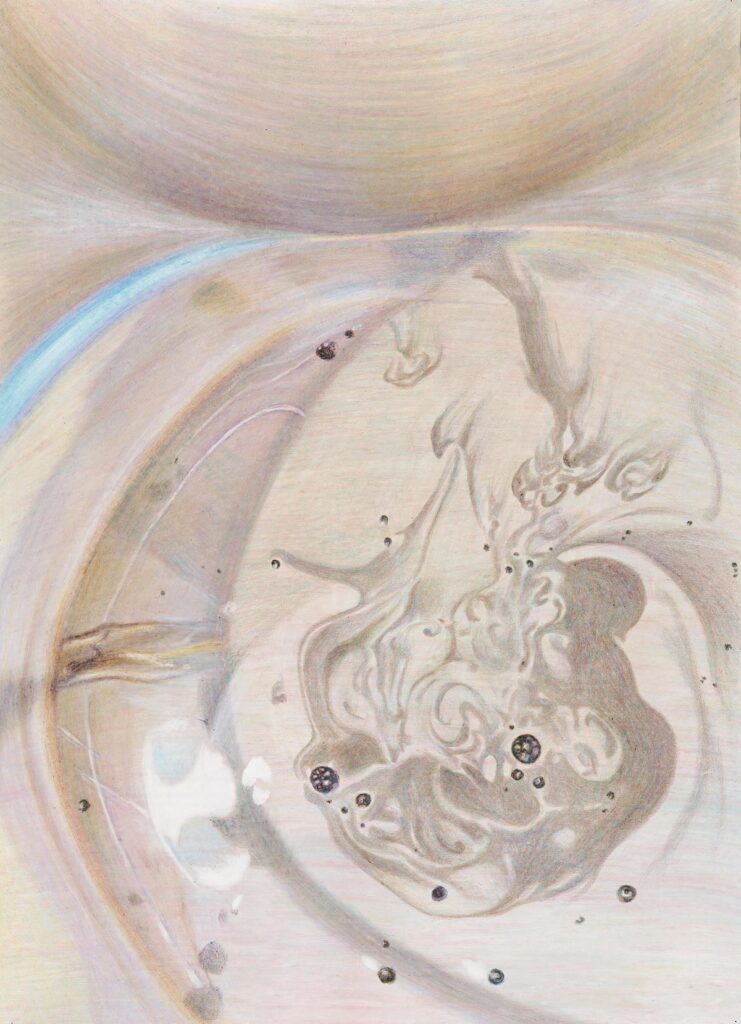

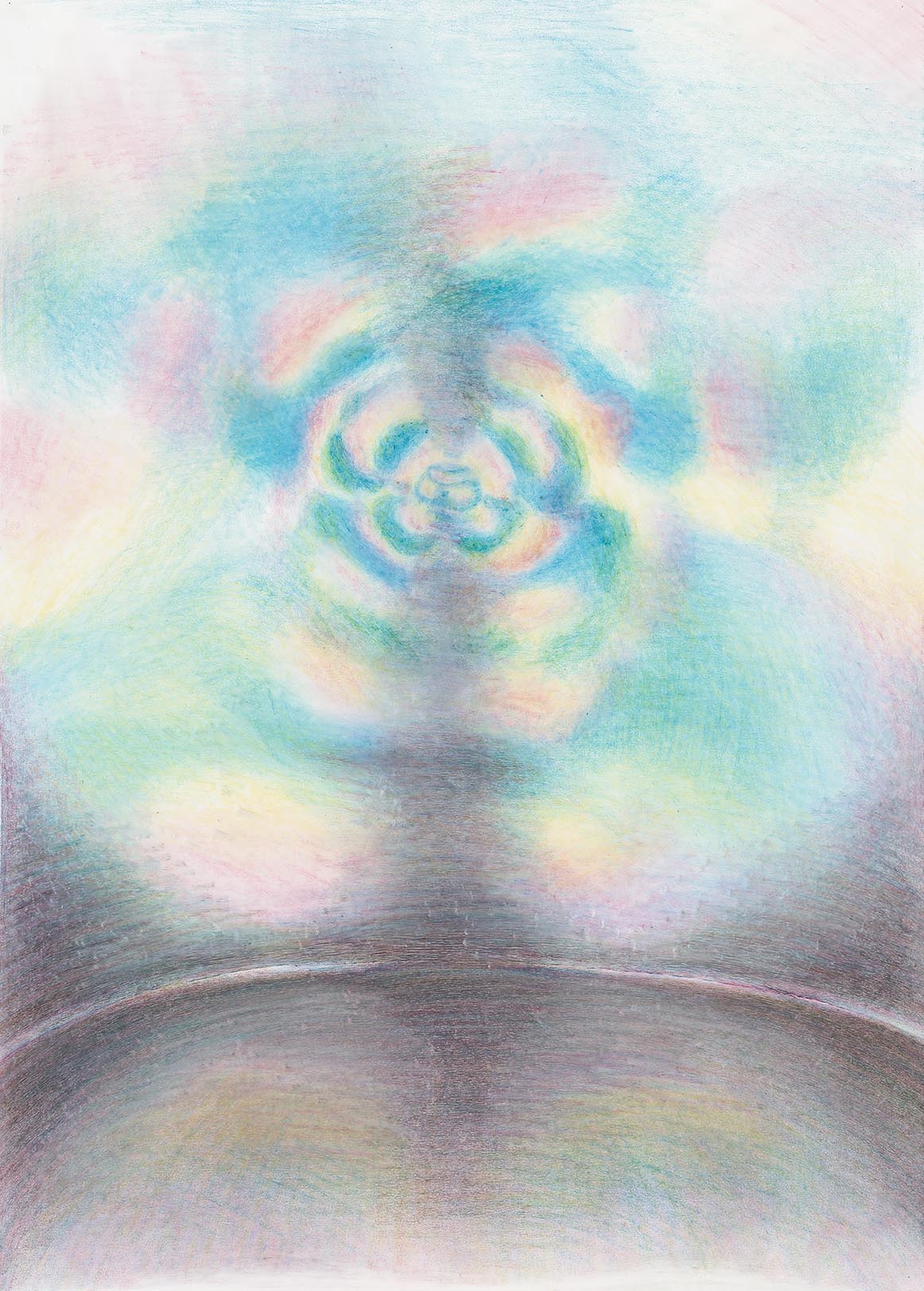

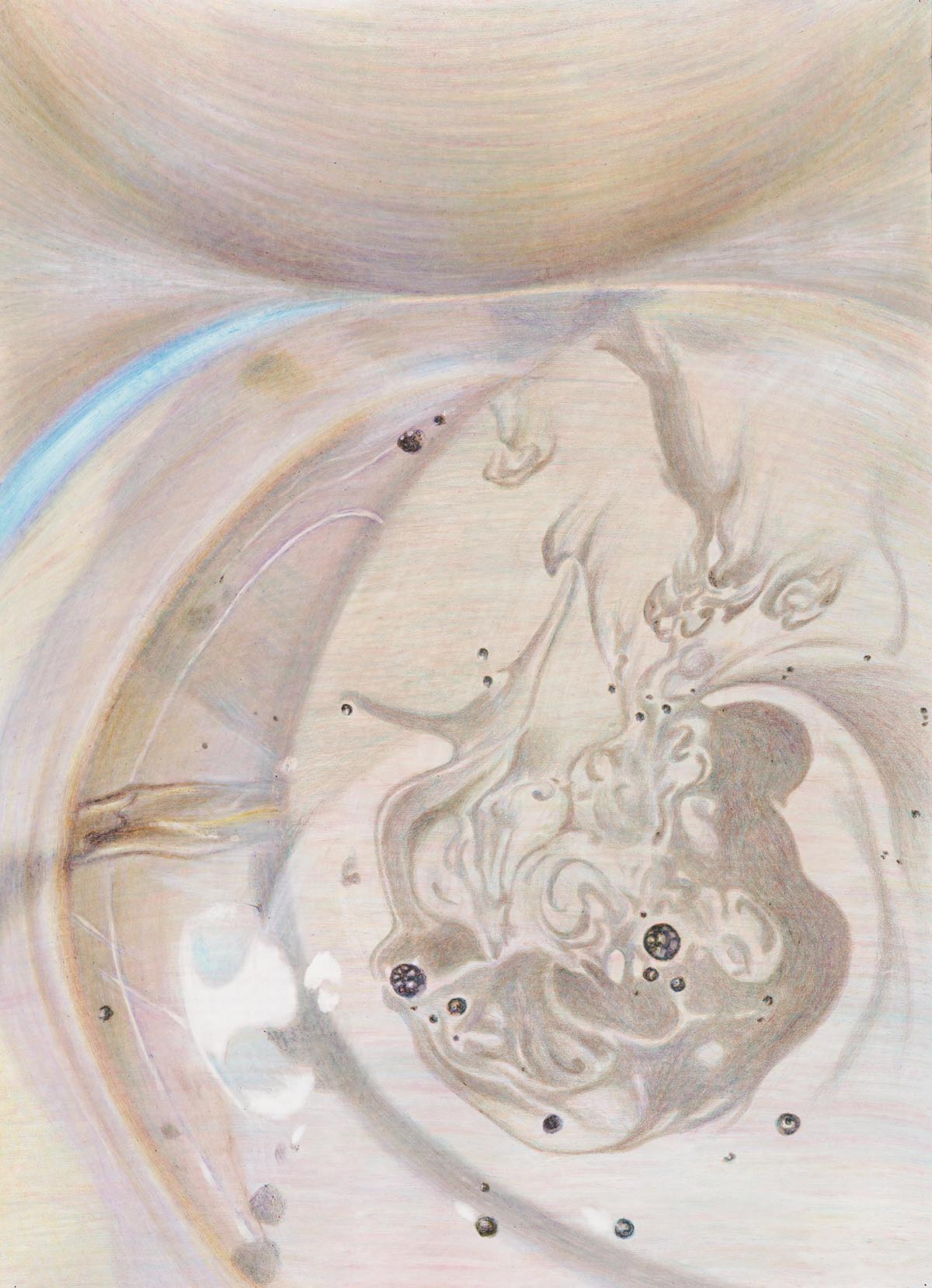

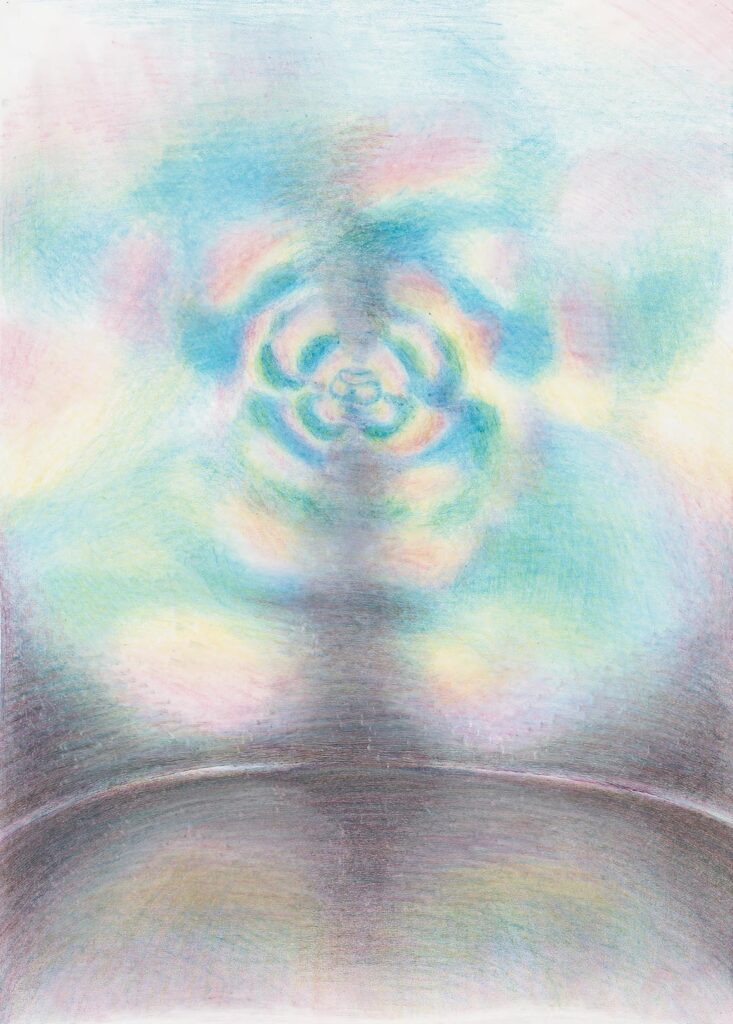

Alphabet of intermediate states, runes from before history, and codex of inter-regna, the things of Oleg de La Morinerie oscillate. Even though they are particularly frozen. They oscillate while frozen. In their primary, agreste state, they stand apart from mere touches, from prototypes of beings, conceived through drawing. Things that let us glimpse or predict the particularities of bodies before their acme, in germination and doubling, in full vitality, and without any determined adornment. Without the thought of adornment. In pure soaring. Neither nor, no no, unclassifiable forms of borders, otherworlds, and scattered lines.

Mathieu Buard

Looking at your large, colorful drawings, can we say they are more like landscapes?

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, it’s a bit like that. They are at once miniature details...

Mathieu Buard

Like textures?

Oleg de La Morinerie

More like patterns that I capture in a blink, that I photograph or quickly sketch. And even in this kind of graphic work, there’s a landscape aspect.

Mathieu Buard

So, if I understand correctly, you observe things in reality that move or strike you, you photograph or draw them, and it’s at that moment they become patterns for you.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, they become patterns, then they start communicating with each other, exchanging characteristics.

Mathieu Buard

And they compose themselves rather quickly, forming a constellation on the page. Often, you perceive a horizon line or a distant star. When I speak of constellations or cosmos, there’s a spatial tension, an organization reminiscent of the image of space. These patterns seem to radiate like stars, composing a landscape, even if it’s not necessarily ours. Is that accurate?

Oleg de La Morinerie

The idea is that it’s identifiable as a macrocosm or a microcosm… Infinitely large, infinitely small… that one traverses the other. To have this porosity, the materiality of the object has to be a bit evanescent so the images can pass through each other.

Mathieu Buard

It’s as if the evanescence of the very fine contour allows for a multitude of internal figurations.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Exactly. There’s a concatenation of images. This principle resembles the functioning of visual memory: through progressive compression, a very rich emotion is born, to the point where you can no longer clearly define it. To the point where you imagine it comes from space when it’s actually very concrete, very tangible. It’s something you truly see. Very concrete, like the technique of the line, of the hatch, which itself forms a pattern within the pattern. A life of its own.

Mathieu Buard

In this vibration, there is indeed a kind of life, like the mycelium in the soil that traverses the entire earth, running parallel to the visible life of the mushroom. In your lines, it feels as if there’s a weaving of life. In this sense, I find it very landscape-like; we enter the tangible materiality of the landscape. It doesn’t matter whether it’s sky, ground, or black hole—it’s interesting. This graphic vibration is very concrete. What exactly is it composed of?

Oleg de La Morinerie

The vibration is composed… never quite an infinite sum of fibers, lines, marks. They are lines, but they leave tiny specks of color on the glossy paper. As soon as it’s drawn, the line slightly disappears, it “sprinkles” lightly, like charcoal. Like in the drawings of Georges Seurat, where there’s this kind of dusting effect. But here it’s different, because it’s made with beeswax, almost greasy without being completely so. It doesn’t create as much dust as charcoal, but it deposits little specks that stick to the paper, and sometimes I can crush them slightly. And when different lines overlap, these specks clump together and create all kinds of transversal patterns.

Mathieu Buard

Inside these lines, there are even more patterns? That’s what’s enigmatic, because ultimately, what we see with the naked eye on the page is just a line. But up close, almost under a magnifying glass…

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, with the naked eye, as you get closer, you can lose sight of the initial line because it’s so subtle.

Mathieu Buard

A microscopic quality of the line, an infinite series of tiny, finely adjusted dots. That gives another particular dimension to the space. Do you know Flatland? That book, where the dimensions shift according to multidimensional geometry, moving from 3D to 2D, then from the line to the point. There’s a political-geometric hierarchy, and it’s amusing that in your work, the dusting of the line, this microscopic quality, is at the very heart of your drawing. Without hierarchy. And with little relief. Little perspective.

Oleg de La Morinerie

There’s little volume, little relief. Or very succinctly. There are atmospheric perspectives, but they’re minimal, in the sense that it’s just the pattern that creates a kind of perspectival frame. Well, when we draw the lines, there is indeed a vanishing point at the center. And sometimes the pattern almost draws a vanishing point.

Mathieu Buard

Yes, but don’t you think it’s like the horizon? This ball, this sphere, it always occupies a floating position in relation to the overall context; it’s not anchored. There’s no shadow.

Oleg de La Morinerie

There is a shadow, but it’s placed on a surface that’s not necessarily the same as the one defined by the vanishing points. It’s not solid like a fact. There’s no gravity, no gravity or solid construction. No coherence.

“The Outer Ones are doubtless the most marvellous organic entities in existence, whether within or beyond the bounds of space and time — members of an intergalactic race of which all other forms of life are but degenerate variants. They are more akin to vegetable than to animal, if such terms can be applied to the sort of matter composing them, and their structure is more or less fungoid; though the presence of a chlorophyll-like substance and a rather singular nutritive system sets them radically apart from the cormophytic fungi of Earth. In truth, their species is formed of a type of matter wholly alien to our region of space — matter whose electrons vibrate at a frequency fundamentally divergent from ours.”

- P. Lovecraft, The Whisperer in Darkness

Mathieu Buard

Mental landscapes. And I start there because, by contrast — obviously, it’s probably the nature of all sculptures when they are in a tangible, solid state like this, and why not covered in mesh, why not covered in skin — it’s never a landscape, it’s always an object. A world folded in on itself. That’s where it appears as sculpture. Meaning that in this sense, it’s a very organized declination, on the contrary, but often in symmetry. It’s as if it were a pattern floating in the absolute. For me, these sculptures are subjects, whereas your drawings are landscapes.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, drawings would be the energetic model of the sculptures, which, starting from there, then materialize and take their concrete form through interaction with matter. The sculptures are the product of these logics. In fact, it’s not sculpture, it’s really modeling. The form isn’t carved; nothing is imposed on the material — the material unfolds on its own. So really, it’s almost not me who creates the form. And in this symmetry model, there only are soft finger pressures. Incompatibilities present in the drawing that, upon contact with matter, give something that seems extremely concrete and detailed to us, but which in fact is not really the work of a sculptor.

Mathieu Buard

You mean it’s like three-dimensional drawing, within the material?

Oleg de La Morinerie

Drawing within the material, or the intensities that enter the drawing and unfold within the material, that inform it. The action represented in the drawing is carried by the material, and yet it materializes very differently.

Mathieu Buard

And it’s different because this material reacts with its own specific properties, which belong to our real world. And yet it creates something that is real and at the same time very unsettling, not so familiar? If I go back to Freud’s words, there’s something, even though it’s symmetrical, that evokes what we find in Alien, for example. Something unsettling, almost symmetrical, or too perfect.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, that’s right, it’s true. But maybe it’s just a matter of judgment, not the truth of the material. But in general, natural forms are quite frightening, at least up close, like internal organs.

Mathieu Buard

It’s more like a particular proximity or circulation with forms that would reveal the strangeness we can see in the forms of the living world or the forms of the world in general. Because you focus on that. Like the drawing that creates a very distant space, we’re talking about space, constellations — it’s micro/macro — and here it’s as if it’s no longer micro or macro, but a focus on materiality. So you’re at the scale of the material. Whereas with drawing and line, it’s abstract, there’s no scale, it’s theoretical. Here, you’re indeed pointing to things like buds that can be disgusting before they bloom, or like a kitten coming out of its placenta, any organism not yet matured, in metamorphosis, potentially repugnant.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, it’s a kind of fluidity that belongs to gestation or entrails. And once it comes out, confronted with the outside world, the forms are forced to rationalize themselves or freeze under the effects of physics.

Mathieu Buard

It freezes. But can we say that’s where it becomes obscene, because it subverts the codes, because it’s not about seduction? It’s material unfolding, unlike a flower or a butterfly…

Oleg de La Morinerie

It’s an efficiency of matter that hasn’t yet given up its biological power.

Mathieu Buard

So, the blossoming of a flower is its death. It’s the moment of blooming, more than magnificence or stability.

It’s very floral, proto-floral. The point of agreement, especially for things like flowers, which end up becoming disappointing or indeed pass through entropy or even negentropy. The object of a death, or at least an end, is really interesting. And then, in the sculptural elements, often placed directly on the ground but also composed on a support — what are these tiers and these layers? Again, it’s like the floral that blooms… Is it a reinterpretation of the notion of sculpture-base? What strikes me in the examples of this series photographed for the magazine is that they look like kinds of bodies placed on little boards. And then, as if there were a slightly retracted skin, a net, several coats or membranes… Like when you love one or more pieces of music. What’s striking is that these are forms resembling shells, always between animal and plant, like in a strange inter-kingdom. Do you feel you’re looking for registers of forms that aren’t worn out? Not the cliché fruit-flower-figurative object, but rather the inter-kingdoms: mineral-plant, plant-animal…

Oleg de La Morinerie

If these are somewhat embryonic forms, they can’t exist outside. So they need a space created for them, a sort of display. Hence the globe, for example. It’s like in the Alien lab — the place with the liquid where the body grows in a hybrid way. It’s a kind of generic lifeform. And there’s also a link with the inanimate and the mineral. Because the end of life can also be considered one of the forms of Earth’s entropy. The pedosphere is the interaction between all environments: light, atmosphere, mineral soil, the oceans. And at that level, there’s a thin layer where all the physical forces interact and where life is born. And so, the shapes, the visuals displayed by a butterfly, a peacock, or a bird actually represent life, sometimes almost figuratively. I try to place myself at that same level… we are the fruit of the fruit.

Mathieu Buard

On botany, if I return to our initial subject, what interests me is not so much the natural classification or the typology drawn from the world’s vocabulary, but rather the variety, the diversity, the formal repertoire that it offers. One can find a repertoire there to make a playful reference, to use your expression. Your work really seems to make sense from that angle, in this strange laboratory where you freeze a very precise moment in the evolution of a form.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, the principle of speciation. Even in writing for example, there’s a bit of that. They’re etymological games, almost genetic, in the way I can write. Little pieces of code move from one sentence to another; the meaning emerges from games of composition, figures of speech. I can rewrite the same sentence several times by shifting these pieces. The logics guiding this are logics of composition and diversification. Of course, I’m also interested in the meaning that this creates each time. There’s a bit of the logics of writing, of surrealist automatism, it’s a bit like automatic writing. There are a lot of slips. May be too much.

Mathieu Buard

You rarely mention the pictorial medium or traditional concepts. You don’t seem to engage with the usual jargon of representation or imagery. What interests you doesn’t seem to be representation in the strict sense. You speak more about energy, of composition arising from that energy, rather than about a represented or figured subject. You distance yourself from everything that is too direct. When you talk about concatenation, you describe well this phenomenon of interpretations that nest together and fix a precise moment, rather than an object or figure identifiable as a face or a flower.

In this sense, you produce a different type of image, not fascinated by theatrical representation.

Oleg de La Morinerie

It’s almost like letters, signs. Although they figure something, their logic is more akin to that of alphabetic writing or ideograms. The ideogram, with a strong evocative power without direct figuration. I invented a word for this: the “caleidées.” It comes from “kalos,” which means “beautiful.” They are ideas that take shape as images, but they are more like mental images, not directly figurative. To materialize the idea rather than represent it, like the forms of a codex.

Alphabet of intermediate states, runes from before history, and codex of inter-regna, the things of Oleg de La Morinerie oscillate. Even though they are particularly frozen. They oscillate while frozen. In their primary, agreste state, they stand apart from mere touches, from prototypes of beings, conceived through drawing. Things that let us glimpse or predict the particularities of bodies before their acme, in germination and doubling, in full vitality, and without any determined adornment. Without the thought of adornment. In pure soaring. Neither nor, no no, unclassifiable forms of borders, otherworlds, and scattered lines.

Mathieu Buard

Looking at your large, colorful drawings, can we say they are more like landscapes?

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, it’s a bit like that. They are at once miniature details...

Mathieu Buard

Like textures?

Oleg de La Morinerie

More like patterns that I capture in a blink, that I photograph or quickly sketch. And even in this kind of graphic work, there’s a landscape aspect.

Mathieu Buard

So, if I understand correctly, you observe things in reality that move or strike you, you photograph or draw them, and it’s at that moment they become patterns for you.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, they become patterns, then they start communicating with each other, exchanging characteristics.

Mathieu Buard

And they compose themselves rather quickly, forming a constellation on the page. Often, you perceive a horizon line or a distant star. When I speak of constellations or cosmos, there’s a spatial tension, an organization reminiscent of the image of space. These patterns seem to radiate like stars, composing a landscape, even if it’s not necessarily ours. Is that accurate?

Oleg de La Morinerie

The idea is that it’s identifiable as a macrocosm or a microcosm… Infinitely large, infinitely small… that one traverses the other. To have this porosity, the materiality of the object has to be a bit evanescent so the images can pass through each other.

Mathieu Buard

It’s as if the evanescence of the very fine contour allows for a multitude of internal figurations.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Exactly. There’s a concatenation of images. This principle resembles the functioning of visual memory: through progressive compression, a very rich emotion is born, to the point where you can no longer clearly define it. To the point where you imagine it comes from space when it’s actually very concrete, very tangible. It’s something you truly see. Very concrete, like the technique of the line, of the hatch, which itself forms a pattern within the pattern. A life of its own.

Mathieu Buard

In this vibration, there is indeed a kind of life, like the mycelium in the soil that traverses the entire earth, running parallel to the visible life of the mushroom. In your lines, it feels as if there’s a weaving of life. In this sense, I find it very landscape-like; we enter the tangible materiality of the landscape. It doesn’t matter whether it’s sky, ground, or black hole—it’s interesting. This graphic vibration is very concrete. What exactly is it composed of?

Oleg de La Morinerie

The vibration is composed… never quite an infinite sum of fibers, lines, marks. They are lines, but they leave tiny specks of color on the glossy paper. As soon as it’s drawn, the line slightly disappears, it “sprinkles” lightly, like charcoal. Like in the drawings of Georges Seurat, where there’s this kind of dusting effect. But here it’s different, because it’s made with beeswax, almost greasy without being completely so. It doesn’t create as much dust as charcoal, but it deposits little specks that stick to the paper, and sometimes I can crush them slightly. And when different lines overlap, these specks clump together and create all kinds of transversal patterns.

Mathieu Buard

Inside these lines, there are even more patterns? That’s what’s enigmatic, because ultimately, what we see with the naked eye on the page is just a line. But up close, almost under a magnifying glass…

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, with the naked eye, as you get closer, you can lose sight of the initial line because it’s so subtle.

Mathieu Buard

A microscopic quality of the line, an infinite series of tiny, finely adjusted dots. That gives another particular dimension to the space. Do you know Flatland? That book, where the dimensions shift according to multidimensional geometry, moving from 3D to 2D, then from the line to the point. There’s a political-geometric hierarchy, and it’s amusing that in your work, the dusting of the line, this microscopic quality, is at the very heart of your drawing. Without hierarchy. And with little relief. Little perspective.

Oleg de La Morinerie

There’s little volume, little relief. Or very succinctly. There are atmospheric perspectives, but they’re minimal, in the sense that it’s just the pattern that creates a kind of perspectival frame. Well, when we draw the lines, there is indeed a vanishing point at the center. And sometimes the pattern almost draws a vanishing point.

Mathieu Buard

Yes, but don’t you think it’s like the horizon? This ball, this sphere, it always occupies a floating position in relation to the overall context; it’s not anchored. There’s no shadow.

Oleg de La Morinerie

There is a shadow, but it’s placed on a surface that’s not necessarily the same as the one defined by the vanishing points. It’s not solid like a fact. There’s no gravity, no gravity or solid construction. No coherence.

“The Outer Ones are doubtless the most marvellous organic entities in existence, whether within or beyond the bounds of space and time — members of an intergalactic race of which all other forms of life are but degenerate variants. They are more akin to vegetable than to animal, if such terms can be applied to the sort of matter composing them, and their structure is more or less fungoid; though the presence of a chlorophyll-like substance and a rather singular nutritive system sets them radically apart from the cormophytic fungi of Earth. In truth, their species is formed of a type of matter wholly alien to our region of space — matter whose electrons vibrate at a frequency fundamentally divergent from ours.”

- P. Lovecraft, The Whisperer in Darkness

Mathieu Buard

Mental landscapes. And I start there because, by contrast — obviously, it’s probably the nature of all sculptures when they are in a tangible, solid state like this, and why not covered in mesh, why not covered in skin — it’s never a landscape, it’s always an object. A world folded in on itself. That’s where it appears as sculpture. Meaning that in this sense, it’s a very organized declination, on the contrary, but often in symmetry. It’s as if it were a pattern floating in the absolute. For me, these sculptures are subjects, whereas your drawings are landscapes.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, drawings would be the energetic model of the sculptures, which, starting from there, then materialize and take their concrete form through interaction with matter. The sculptures are the product of these logics. In fact, it’s not sculpture, it’s really modeling. The form isn’t carved; nothing is imposed on the material — the material unfolds on its own. So really, it’s almost not me who creates the form. And in this symmetry model, there only are soft finger pressures. Incompatibilities present in the drawing that, upon contact with matter, give something that seems extremely concrete and detailed to us, but which in fact is not really the work of a sculptor.

Mathieu Buard

You mean it’s like three-dimensional drawing, within the material?

Oleg de La Morinerie

Drawing within the material, or the intensities that enter the drawing and unfold within the material, that inform it. The action represented in the drawing is carried by the material, and yet it materializes very differently.

Mathieu Buard

And it’s different because this material reacts with its own specific properties, which belong to our real world. And yet it creates something that is real and at the same time very unsettling, not so familiar? If I go back to Freud’s words, there’s something, even though it’s symmetrical, that evokes what we find in Alien, for example. Something unsettling, almost symmetrical, or too perfect.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, that’s right, it’s true. But maybe it’s just a matter of judgment, not the truth of the material. But in general, natural forms are quite frightening, at least up close, like internal organs.

Mathieu Buard

It’s more like a particular proximity or circulation with forms that would reveal the strangeness we can see in the forms of the living world or the forms of the world in general. Because you focus on that. Like the drawing that creates a very distant space, we’re talking about space, constellations — it’s micro/macro — and here it’s as if it’s no longer micro or macro, but a focus on materiality. So you’re at the scale of the material. Whereas with drawing and line, it’s abstract, there’s no scale, it’s theoretical. Here, you’re indeed pointing to things like buds that can be disgusting before they bloom, or like a kitten coming out of its placenta, any organism not yet matured, in metamorphosis, potentially repugnant.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, it’s a kind of fluidity that belongs to gestation or entrails. And once it comes out, confronted with the outside world, the forms are forced to rationalize themselves or freeze under the effects of physics.

Mathieu Buard

It freezes. But can we say that’s where it becomes obscene, because it subverts the codes, because it’s not about seduction? It’s material unfolding, unlike a flower or a butterfly…

Oleg de La Morinerie

It’s an efficiency of matter that hasn’t yet given up its biological power.

Mathieu Buard

So, the blossoming of a flower is its death. It’s the moment of blooming, more than magnificence or stability.

It’s very floral, proto-floral. The point of agreement, especially for things like flowers, which end up becoming disappointing or indeed pass through entropy or even negentropy. The object of a death, or at least an end, is really interesting. And then, in the sculptural elements, often placed directly on the ground but also composed on a support — what are these tiers and these layers? Again, it’s like the floral that blooms… Is it a reinterpretation of the notion of sculpture-base? What strikes me in the examples of this series photographed for the magazine is that they look like kinds of bodies placed on little boards. And then, as if there were a slightly retracted skin, a net, several coats or membranes… Like when you love one or more pieces of music. What’s striking is that these are forms resembling shells, always between animal and plant, like in a strange inter-kingdom. Do you feel you’re looking for registers of forms that aren’t worn out? Not the cliché fruit-flower-figurative object, but rather the inter-kingdoms: mineral-plant, plant-animal…

Oleg de La Morinerie

If these are somewhat embryonic forms, they can’t exist outside. So they need a space created for them, a sort of display. Hence the globe, for example. It’s like in the Alien lab — the place with the liquid where the body grows in a hybrid way. It’s a kind of generic lifeform. And there’s also a link with the inanimate and the mineral. Because the end of life can also be considered one of the forms of Earth’s entropy. The pedosphere is the interaction between all environments: light, atmosphere, mineral soil, the oceans. And at that level, there’s a thin layer where all the physical forces interact and where life is born. And so, the shapes, the visuals displayed by a butterfly, a peacock, or a bird actually represent life, sometimes almost figuratively. I try to place myself at that same level… we are the fruit of the fruit.

Mathieu Buard

On botany, if I return to our initial subject, what interests me is not so much the natural classification or the typology drawn from the world’s vocabulary, but rather the variety, the diversity, the formal repertoire that it offers. One can find a repertoire there to make a playful reference, to use your expression. Your work really seems to make sense from that angle, in this strange laboratory where you freeze a very precise moment in the evolution of a form.

Oleg de La Morinerie

Yes, the principle of speciation. Even in writing for example, there’s a bit of that. They’re etymological games, almost genetic, in the way I can write. Little pieces of code move from one sentence to another; the meaning emerges from games of composition, figures of speech. I can rewrite the same sentence several times by shifting these pieces. The logics guiding this are logics of composition and diversification. Of course, I’m also interested in the meaning that this creates each time. There’s a bit of the logics of writing, of surrealist automatism, it’s a bit like automatic writing. There are a lot of slips. May be too much.

Mathieu Buard

You rarely mention the pictorial medium or traditional concepts. You don’t seem to engage with the usual jargon of representation or imagery. What interests you doesn’t seem to be representation in the strict sense. You speak more about energy, of composition arising from that energy, rather than about a represented or figured subject. You distance yourself from everything that is too direct. When you talk about concatenation, you describe well this phenomenon of interpretations that nest together and fix a precise moment, rather than an object or figure identifiable as a face or a flower.

In this sense, you produce a different type of image, not fascinated by theatrical representation.

Oleg de La Morinerie

It’s almost like letters, signs. Although they figure something, their logic is more akin to that of alphabetic writing or ideograms. The ideogram, with a strong evocative power without direct figuration. I invented a word for this: the “caleidées.” It comes from “kalos,” which means “beautiful.” They are ideas that take shape as images, but they are more like mental images, not directly figurative. To materialize the idea rather than represent it, like the forms of a codex.